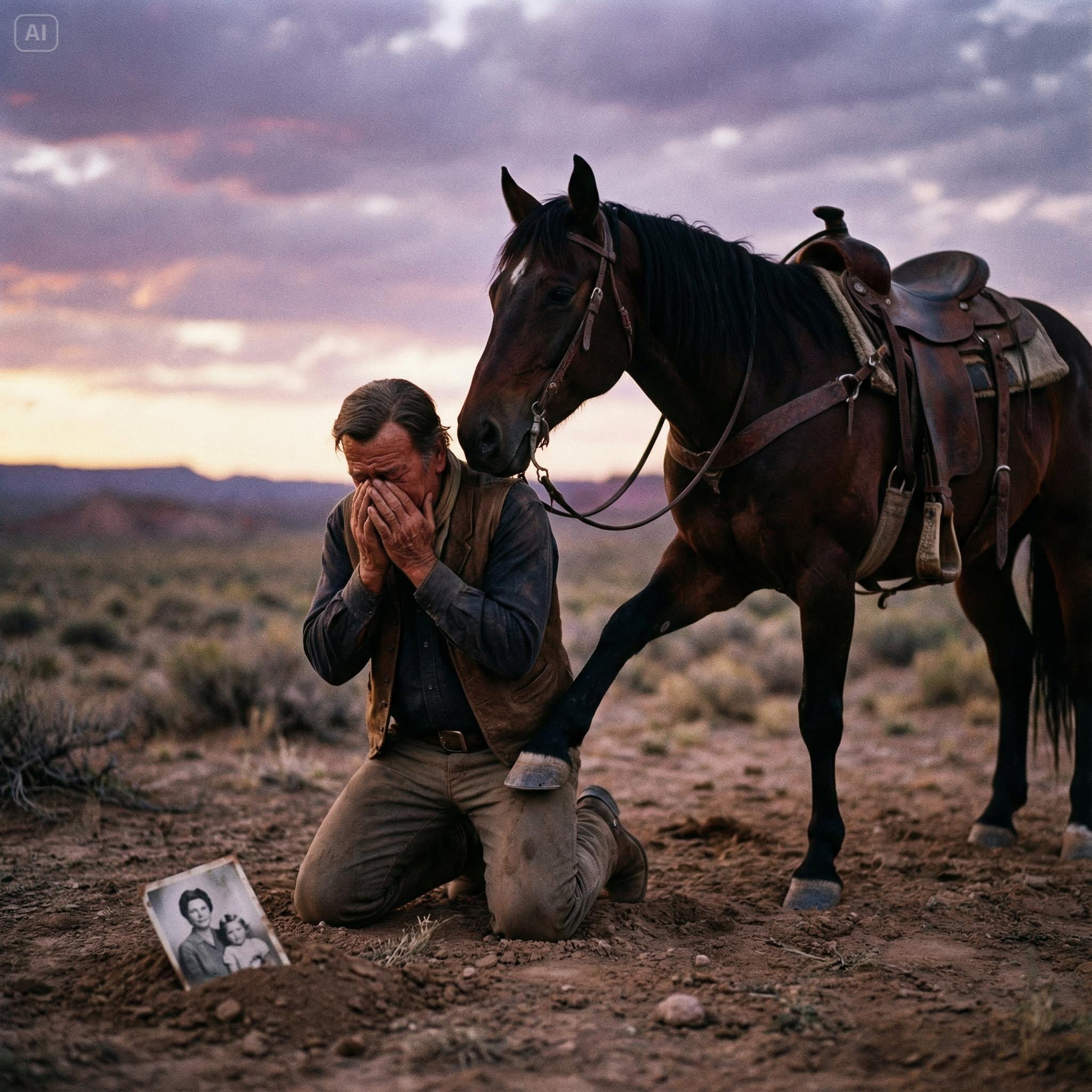

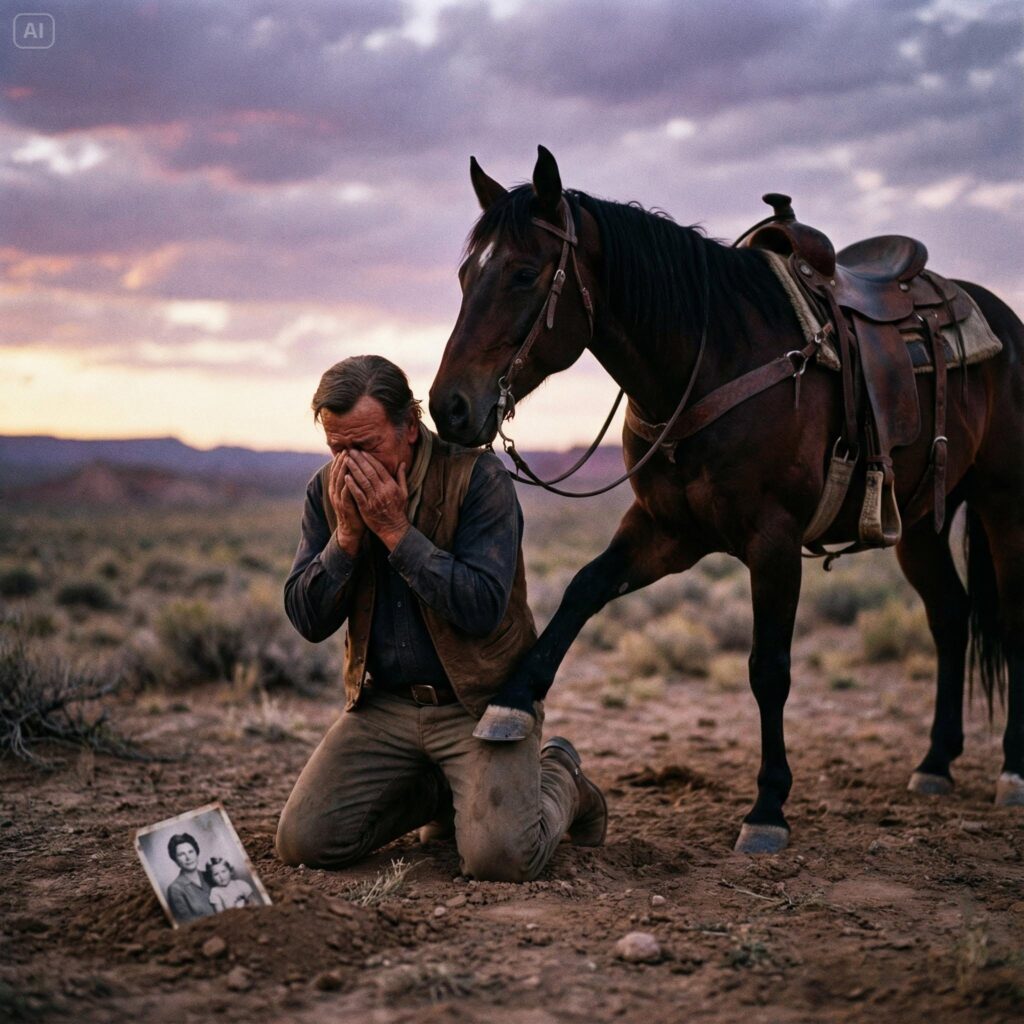

The set went quiet. The cameras had stopped rolling and John Wayne’s horse refused to leave him. Monument Valley, Utah. September 1976. The late afternoon sun cast long shadows across the red dirt of a western film set that had seen a thousand sunsets just like this one. The wooden storefronts of a frontier town stood silent, their false facads catching the golden light.

The crew was packing equipment. Cameras wheeled back, light stands collapsed. The familiar end of day ritual of a production wrapping for the evening. It should have been just another day. Just another scene finished. Just another ride completed. But the horse knew. Animals know things we pretend not to see. They feel what we hide.

And this horse, a chestnut gelling named Dollar who had carried John Wayne through 32 years of film work, knew something the crew didn’t. something Wayne himself was trying not to acknowledge. The scene had wrapped 15 minutes ago. A simple shot. Wayne riding into town, dismounting at the hitching post, delivering three lines to the sheriff. Standard work.

They’d gotten it in two takes. The director had called cut, thanked everyone, moved on to setting up the next location. Wayne sat in the saddle, reigns loose in his weathered hands, making no move to dismount. The wranglers waited nearby, ready to take Dollars, but Wayne didn’t move. He just sat there, one hand resting on the horse’s neck, looking out at the valley beyond the set.

“John,” the assistant director approached carefully.

“We’re good on this setup. You can head to your trailer if you want.”

Wayne nodded slowly but still didn’t dismount. His jaw was set in that familiar line, the expression that had defined a thousand movie posters, the face of American stoicism. But something in his eyes was different today.

Finally, he swung his leg over and stepped down. His boots hit the dust with a soft thud. He moved slower than he used to. 70 years old now. His body carrying the weight of decades of stunts and hard riding and a lifestyle that had never been gentle. He released the res started to turn toward his trailer. Dollar didn’t move.

The horse stood perfectly still, watching Wayne walk away. Then, as Wayne took his third step, Dollar did something he never done in three decades of working together. He followed, not led, not called. He simply walked after Wayne, closing the distance, and pressed his head firmly against the man’s back. Wayne stopped, turned, put his hand on Dollar’s face.

“I know, old son,” Wayne said quietly.

“I know,” Wayne didn’t raise his voice.

“He didn’t have to.” The crew members who were close enough to see stopped what they were doing. The Wranglers froze. Everyone understood on some instinctive level that they were witnessing something beyond a man and his horse. They were watching goodbye.

Wayne had been diagnosed 6 months earlier. Lung cancer, stage 4, the same disease that had taken his friend Gary Cooper that had hollowed out so many men of his generation who’d spent their lives smoking on film sets and in dressing rooms. He hadn’t told anyone outside his immediate family and his doctor.

Not the studio, not the producers, not the crew. He’d kept working because work was what John Wayne did. You showed up. You did the job. You didn’t complain. But cancer doesn’t care about stoicism. And by September 1976, Wayne was running out of time. His body was betraying him in small ways. the breathlessness after takes, the tightness in his chest, the weight he couldn’t keep on.

He’d gotten through this picture on pure will, but everyone close to him could see it was becoming harder. Everyone, apparently, including his horse. Dollar pressed harder against Wayne’s chest, not aggressively, but insistently. The horse’s ears were forward, his eyes soft. He made a low sound, not quite a winnie, more like a question.

Wayne’s weathered hand moved along Dollar’s neck with a gentleness that contrasted sharply with his tough guy screen image. His jaw clenched, his eyes glistened. For just a moment, the mask slipped, and everyone watching saw not John Wayne, the movie star, but Marian Morrison, the man, scared, tired, facing something he couldn’t outdraw or outride.

“You’ve been a good partner,” Wayne said, his voice rough. Best I ever had. The head wrangler, Tom Hedley, who had worked with Wayne since 1944, approached slowly. He trained dollar specifically for Wayne back in 1944, matched them deliberately because both had the same temperament, steady, reliable, no flash, but absolute substance.

John, Tom said quietly. He doesn’t want to go. I know. He’s never done this before. 32 years. I’ve never seen him refuse to leave you. Wayne nodded. He understood what Tom wasn’t saying. Horses know. They feel heartbeats, sense illness, recognize when their humans are struggling. Dollar knew Wayne was sick even if Wayne wouldn’t say the word out loud.

The director, Andrew McLaglin, who had directed Wayne in nine pictures, stood at a respectful distance. He noticed Wayne struggling all week. The way he’d grip his chest between takes. The way he’d sit in his chair longer than usual, catching his breath. He’d said nothing because Wayne wouldn’t have tolerated the concern.

But now, watching this moment between man and horse, Andrew made a decision.

“Clear the set,” he called out.

“Give Mr. Wayne some privacy. Everyone to base camp now.”

The crew moved quickly and quietly, understanding the gift they were being given. permission to witness something sacred without intruding on it.

They walked backward toward the trailers, watching, no one reaching for cameras or trying to document this. Some things shouldn’t be photographed. Some moments belong only to the people and animals living them. Subscribe and leave a comment because the most important part of this story is still unfolding. When the set was empty except for Wayne, Dollar and Tom Hadley standing at a distance, Wayne did something he hadn’t done in decades of film work.

He leaned his forehead against Dollars, closed his eyes, and let himself just breathe. The horse stood perfectly still, holding the weight of the man, patient and solid.

“I’m scared, old son,” Wayne whispered, so quiet only the horse could hear. I’ve played brave my whole life, but I’m scared of this one. Dollar exhaled slowly, his warm breath mixing with Waynees in the cooling desert air.

The sun was dropping toward the horizon now, painting everything gold and red, the colors of every western Wayne had ever made, the landscape that had defined his career and his image. This valley had been Wayne’s second home. He’d filmed here in 1939 with John Ford on Stage Coach, the movie that made him a star.

He’d returned again and again over four decades, riding these same trails, sleeping in these same small hotels, eating at the same diner and Mexican hat. Monument Valley was as much a part of John Wayne as his draw or his walk or the way he wore a hat. And now he was saying goodbye to it, to dollar, to the work that had given his life meaning.

I don’t know how to do this part, Wayne said, still leaning against the horse. I’ve died in plenty of pictures, but I always knew I’d get up when they called cut. This time, he stopped, his voice catching. This time, there’s no cut. Dollar shifted slightly, adjusting to support Wayne’s weight more fully.

His ears swiveled, listening to everything and nothing, just being present the way only animals can be. Tom Headley watched from 50 ft away, tears running down his weathered face. He’d seen Wayne ride through broken bones, through hangovers, through the aftermath of cancer surgery in 1964 when Wayne had beaten it the first time.

He’d seen Wayne work through personal tragedy, divorces, the loss of friends, the changing of an industry that was leaving him behind. But he’d never seen Wayne like this. Vulnerable, admitting fear, letting his guard down completely. Away from the cameras, Wayne made a choice no one expected. Wayne straightened slowly, putting both hands on Dollar’s face.

He looked the horse directly in the eye with that intense gaze that had commanded a million movie screens.

“Listen to me,” Wayne said, his voice steady now, falling into the tone he used when he needed to get through something difficult. You’re going to be okay. Tom’s going to take care of you. You’re going to have a good retirement.

Plenty of pasture. Easy days. You’ve earned it, old son. You’ve done your job. The horse blinked, watching him. And I’m going to do mine. Wayne continued. I’m going to finish this picture. I’m going to show up every day until we rap. I’m going to do it the way I’ve always done it. No complaints, no excuses.

But after that, he paused, gathering himself. After that, I don’t know. Maybe I’ll beat this thing again. Maybe I won’t. But either way, I need you to know something. Wayne’s voice cracked, but he pushed through. You made me better. All those years, all those movies, all those stunts, I could do them because I trusted you.

I never worried, never hesitated, because I knew you’d be there. You made me look like a hero, but we both know the truth. You were the hero. I was just along for the ride. Tom Hadley covered his mouth with his hand, trying not to sob out loud. Wayne reached into his vest pocket and pulled out something small. A sugar cube, the kind he’d carry for Dollar since 1944, a ritual between them that predated most of the people on this set. He held it out.

Dollar took it gently. the familiar transaction that had marked the end of a thousand riding days.

“Good boy,” Wayne said softly.

“Good boy.”

He kissed the horse’s nose, a gesture so tender and so private that Tom almost looked away. Then Wayne stepped back, picked up his hat from where he’d set it on the hitching post, and settled it on his head with that familiar gesture that had closed a 100 movies.

“Tom,” he called out, his voice back to its normal commanding tamber.

“Take him on back. Make sure he gets extra oats tonight.”

Tom approached, taking dollar’s reigns. The horse resisted for a moment, still watching Wayne, still not wanting to leave. But Tom was gentle, persistent, and finally Dollar allowed himself to be led away, looking back over his shoulder three times before disappearing behind the false front buildings.

Wayne stood alone in the empty set in the failing light watching his horse go. The crew observing from base camp saw him there, a silhouette against the red rocks, perfectly still, the image of cowboy stoicism. None of them would ever forget it. But what followed would stay with everyone who witnessed it forever. Wayne finished the picture.

Three more weeks of shooting. Every day a little harder than the last. But he showed up. He hit his marks. He delivered his lines. He rode other horses when the scenes required it, but everyone noticed he never asked for Dollar again. On the final day of production, Wayne gave Tom Hedley an envelope.

Inside was enough money to ensure Dollar would never want for anything along with a simple handwritten note. Take care of my partner. Tom kept that note until the day he died. It’s framed now in the Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, displayed next to a photograph of Wayne and Dollar from 1944. Young man, young horse, both of them with decades of work ahead of them.

Wayne lived three more years after that September day in Monument Valley. He made one more film, The Shudest, about an aging gunfighter dying of cancer, a role that required no acting at all. He won his only academy award the year before he died. Accepted it with characteristic brevity and spent his final months with his family away from cameras.

Dollar lived six more years in retirement on Tom Hadley’s ranch in California. He had acres of pasture, gentle companionship from other retired movie horses, and every evening Tom would bring him a sugar cube honoring the ritual Wayne had started. When Dollar died in 1982, Tom buried him on the ranch under an oak tree facing west toward Monument Valley.

Share and subscribe. Some stories deserve to be remembered. The moment on the set that day when a horse refused to leave his dying partner became legend among the crew who witnessed it. They told their children, their grandchildren. It passed into the mythology of Hollywood. one of those stories that captures something true about the cost of being John Wayne.

Because here’s what they understood. John Wayne wasn’t a myth. He was a man who showed up and did hard work for 50 years. He built an image of strength not because it came easy, but because he chose it every single day. And on that September afternoon in Monument Valley, when his horse refused to leave him, Wayne showed the truest strength of all.

He let himself be afraid. He let himself be honest. He said goodbye. The horse knew what Wayne couldn’t say out loud. That this was the end. That the man who had ridden through a thousand sunsets was facing his last one. But even then, Wayne made the choice that defined him. He straightened up, put on his hat, told the horse it would be okay, and he kept working.

Share and subscribe. Some stories deserve to be remembered. Tom Hadley kept the note Wayne gave him for dollars care. It hangs in the Western Heritage Museum now beside a photograph of a young man and a young horse who built a legend together one ride at a time. Dollar is buried facing west toward the valley toward the man he refused to leave.

And somewhere in that red dust and endless sky, you can still feel them. The last ka and the horse who knew his heart.