“Two years in prison won’t kill you, Alice.”

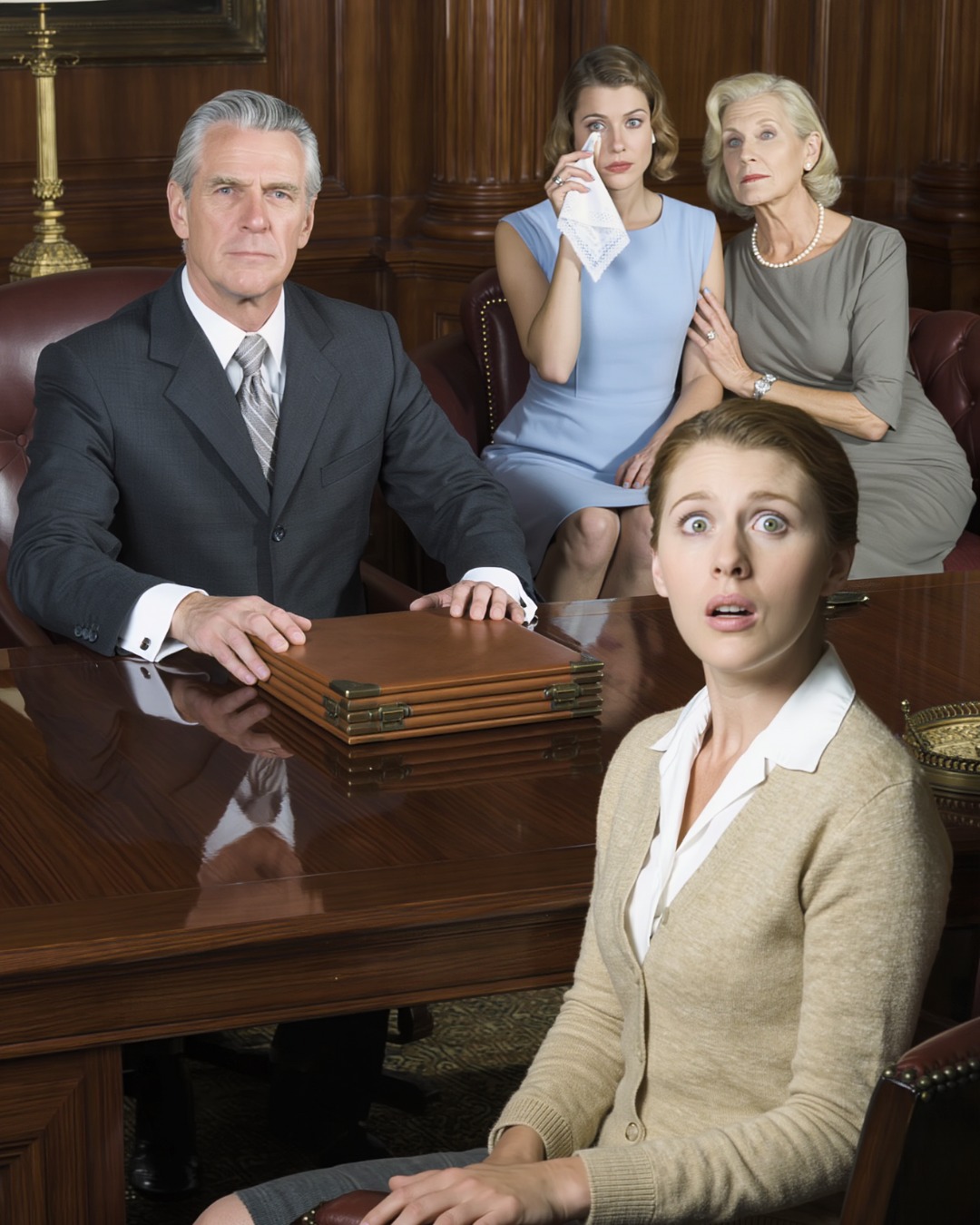

My father said it the way some men order a second cup of coffee—mildly irritated, mildly bored. He sat behind the huge mahogany desk in his study, the one he liked to call “command central,” with the confidence of someone who’d never heard the word “consequences” used in a sentence about him. The yellow desk lamp cast warm light over the thick folder he slid toward me, as casually as if he were passing the salt at dinner.

“Minimum security,” he added, as though that made this more thoughtful. “You’re used to struggling. Nobody looks at you. You’ll be fine.”

The word you had never sounded so sharp.

I looked at the folder, not touching it yet. It was fat. Too fat. The kind of folder that meant years of cheating condensed into paper: bank statements, forged signatures, cooked books, fake invoices. Tax fraud. Embezzlement. Crimes with long names and longer sentences.

On the leather sofa to my right, my sister Beatrice made a sound like a wounded animal. I might have believed it if I didn’t know her. She carefully pressed a white handkerchief to her lower lashes, dabbing away tears before they had a chance to ruin her mascara. Our mother sat beside her, rubbing her back in soothing circles.

“It’s not fair,” Beatrice whispered. “I didn’t mean for it to go this far. Daddy, you promised I’d be okay.”

“I am fixing it,” my father said, his tone tender when he spoke to her, cold granite when he looked at me. “But I can’t fix it without cooperation.”

He said the last word like a warning.

I finally reached for the folder. It was heavier than it looked, or maybe my hands were shaking more than I wanted them to. The name on the first page was Beatrice’s—her company, her accounts, her signature, her mess. Next to her name were numbers that would make any auditor sit up straight. I skimmed through dates, wire transfers, investor names. I recognized some of the banks. I recognized some of the tricks.

I recognized the smell of rot.

“They’ll trace this,” I said quietly, flipping through the pages. “The IRS isn’t completely asleep, you know.”

“That’s why we need a narrative,” my father replied. “A fall person. Someone who… mismanaged things. Someone who can plead guilty, do a short stint, pay a little restitution, and put this behind us.”

“Us,” I repeated.

“Yes, us,” he snapped. “Family.”

Beatrice sniffled louder. “I can’t go to prison,” she whimpered. “The wedding is next month. The Sterlings will call everything off. Harrison’s mother already doesn’t like me, she thinks I’m ‘too creative.’ If this comes out, it will destroy everything.”

There it was. The real emergency. Not the crime. Not the fact that government money had been stolen, that investors had been lied to. The crisis, as far as they were concerned, was a questioned seating chart and a canceled string quartet.

My mother finally looked at me, mascara perfect, lipstick untouched. “Be reasonable, Alice,” she said. “You’re not married. You have no children. You rent. Two years in minimum security, you keep your head down, you get out, and we’ll take care of you. We’ll help you when it’s over.”

I laughed, a short, ugly sound I didn’t quite manage to swallow.

“What?” Mother asked sharply.

“Nothing,” I said. “Go on.”

My father leaned back in his chair, fingers steepled. “You know you owe this family. We’ve carried you for years. We supported you when you couldn’t make anything of yourself. This is your chance to show some gratitude.”

That was almost funny.

They thought I couldn’t make anything of myself. They genuinely believed that. Because it was easier. Because it kept their world tidy: Beatrice the star, Alice the shadow. One bright, one dull. Simple. Symmetrical.

I closed the folder and placed both hands on top of it, pressing lightly, as if I were testing the weight of my own life.

“How long?” I asked.

My father’s eyes gleamed with satisfaction. He mistook my question for surrender. “Sentencing guidelines say eighteen to twenty-four months,” he said. “You plead guilty early, cooperate, show remorse—maybe less. We’ll hire a good lawyer for you.”

I thought of the lawyers my firm dealt with. The ones who billed more per hour than I paid in rent each month. The ones people like my father hired when they needed to twist the knife just right.

My throat felt tight. Not from tears—those had run out years ago—but from something harder, sharper. I knew better than to argue outright. You don’t convince people like my parents. You don’t appeal to their love. You either obey or you become a problem to be solved.

I leaned back in my chair, pretending to shrink into it.

“I need twenty-four hours,” I whispered.

My father frowned. “For what?”

“To think,” I said. “To… get used to the idea. To put some things in order. Please.”

He watched me for a few seconds. I dropped my gaze, let my shoulders curl inward, allowed my fingers to shake around the folder. It wasn’t hard; adrenaline was already flooding my system. I made sure my voice wavered just enough.

“Fine,” he said at last. “But don’t take longer than that. We need to get out ahead of this.”

“We always knew,” my mother added, in that sweet, poisonous tone she used when she wanted to hurt me without ever raising her voice, “that you would come through when it really mattered.”

She stood and walked over to me. For a moment, I thought she was going to hug me. Old habits die hard. Instead, she just patted my shoulder, like I was a secretary who’d agreed to work overtime.

Beatrice sniffled again. “Thank you,” she said thickly. “I’ll never forget this, Alice. I promise. I’ll visit. I’ll send you things. When I’m married, I’ll—”

“You’ll what?” I asked, looking at her. “Put my picture on a shelf?”

Her face crumpled. Mother shot me a warning look.

“That’s enough,” my father muttered. “Go home, get yourself together. Come back tomorrow and we’ll have the lawyer here.”

I stood slowly, folder in hand. My knees felt rubbery, but my spine was oddly straight. I looked at the three of them—the chosen one, the adoring mother, the self-appointed patriarch—and something inside me went cold and very, very still.

They thought they were looking at a frightened girl.

They had no idea who they were actually looking at.

“I’ll be back tomorrow,” I said.

Then I walked out of the study, down the hall decorated with framed family photos in which I was always slightly further from the center of the frame than everyone else, past the front door my father insisted on keeping polished to a mirror shine, and out into the biting evening air.

I didn’t cry.

Not yet.

I got into my car, an aging hatchback with a cracked dashboard and a stubborn engine, and started the ignition. My hands were clamped so tightly around the steering wheel that my knuckles were almost translucent. I drove two blocks, then pulled into the shadow of a closed pharmacy and killed the engine.

The silence hit me harder than my father’s words had.

I let my head fall back against the headrest and stared at the car’s roof. My breaths came in short, shallow bursts, then deeper ones, almost gasps. The world narrowed to the stale smell of fast food wrappers and cheap air freshener, to the faint ticking of cooling metal.

“Two years in prison,” I said out loud, just to hear it. It sounded surreal, like a plot from some crime show playing on a TV in another room.

The thing about a moment like that is, it doesn’t come out of nowhere. It’s not a lightning strike; it’s the final crack in a wall that has been quietly splitting for years. To understand why my parents felt so comfortable sliding a prison sentence across the desk at me like a dinner bill, you’d have to understand the economy of my family.

For twenty-six years, I’d been the spare part.

Not the engine. Not the gleaming hood ornament. The emergency tire in the trunk—useful only in a breakdown, otherwise forgotten.

When Beatrice and I were children, our parents loved to tell the “birth story” at parties. Beatrice’s part was always described in glowing terms: the long-awaited firstborn, the miracle baby, the star. When it came to me, my mother would laugh and say, “Alice was a surprise. We weren’t really planning a second, but… well, she arrived.” People would chuckle, I’d smile politely, and Beatrice would twirl or sing or show off something that made the adults clap.

The hierarchy was established early: Beatrice, brilliant and dazzling and fragile; Alice, sturdy and unremarkable and endlessly replaceable.

When Beatrice failed a math test, there were emergency meetings with the teacher, tearful promises to hire tutors, anguished conversations about how “numbers just aren’t her gift, but she’s so creative.” When I brought home straight A’s, my father glanced at the report card and said, “Good. That’s what’s expected,” before handing it back without further comment.

When she crashed her first car at sixteen—a brand-new convertible my father had surprised her with on her birthday—everyone rushed to comfort her. It wasn’t her fault; the roads were slippery; she was under stress. When I dented the door of my secondhand sedan backing out of the driveway, my father shouted about carelessness and how some people didn’t appreciate what they had.

They poured money into Beatrice’s life like it was a leaky bucket they were determined to keep full at any cost. Private schools. Summer programs abroad. Art classes, dance classes, “entrepreneurial incubators.” When she decided she wanted to “launch a brand” in college, they funded that too. She lasted one semester before dropping out to “focus on her vision.”

The vision changed constantly. The funding never did.

By the time I graduated from high school, it was clear there wasn’t much left for me, financially or emotionally. College was my responsibility. Rent was my responsibility. Survival was my responsibility. When I asked if they could help a little—just a little—with tuition or textbooks, my mother sighed and said, “We wish we could, but things are tight right now. You understand how much we’ve had to do for your sister.”

So I understood. I worked three jobs and ate too many meals consisting of toast and whatever vegetable was on sale that week. I studied whenever I could keep my eyes open. I learned to stretch a dollar until it screamed.

What they never realized—because they never cared enough to ask—was what, exactly, I was studying so hard for.

In their heads, I was a data entry clerk.

That was the story that made sense to them. “Alice works with computers,” they’d say vaguely, when people asked. “Something with numbers. She’s in an office.”

They never asked me for details. In five years, neither of my parents ever said, “So, what exactly do you do all day, Alice?” They didn’t attend any of my professional milestones. They didn’t know my firm’s name. They didn’t know that the clothes I wore when I visited them—the bland cardigans, the sensible flats—were a costume I put on like armor.

In reality, I was a senior forensic auditor for one of the most aggressive litigation firms in the state.

My job wasn’t to type numbers.

My job was to hunt them.

I followed money the way some people followed gossip. I chased it through shell corporations and offshore accounts, through deliberately confusing spreadsheets and carefully arranged “mistakes.” I worked on high-stakes divorce cases and corporate collapses, quietly unthreading the lies rich people told so they could keep more than their fair share.

I was good at it. Very good. Good enough to have my name requested on difficult cases. Good enough to be quietly sought after in certain circles. Good enough that my salary was more than respectable, though you wouldn’t know it from the way I lived.

Why didn’t I live “better”? Why didn’t I flaunt what I had?

Because I knew my parents.

If they saw me thriving, they’d find a way to turn it into a resource for Beatrice. They’d ask for favors, money, contacts. They’d find a way to make my success hers, and when they were done, there’d be nothing left.

So I made myself small. I rented a freezing four-hundred-square-foot studio apartment with unreliable heating. I drove an old car and wore simple clothes. I didn’t post photos of vacations or dinners or anything that might hint at comfort. When I visited my parents, I let them believe I was just scraping by as an “office girl.”

It hurt, at first, that they were so disinterested.

Sitting in my car that night, folder of my sister’s crimes in my lap, I realized their ignorance was the best weapon I’d ever had.

They didn’t understand me. They didn’t know what I did. They didn’t think I was capable of anything more than taking orders and filling out forms.

They thought I was the perfect person to take the fall.

They were wrong.

Rain began to patter on the windshield, first a few scattered drops, then a steady curtain. The pharmacy’s neon sign flickered on, bathing my dashboard in sickly pink light.

My phone buzzed with a text. Dad: “Remember. 6 p.m. tomorrow. Don’t be late.”

As if I had anywhere else to be.

I stared at the message until my vision blurred. Not from tears. From a strange, sharp clarity that was starting to push its way through the fog.

They were going to send me to prison and still expected me to be punctual about it.

“Of course they do,” I muttered.

The truth settled over me in layers.

They didn’t hate me.

I’d wondered that for years—if they secretly despised me, if I’d done something, as a baby, a child, a teenager, to make myself unlovable. I’d twisted myself into knots trying to solve the puzzle of why Beatrice got everything and I got… scraps.

But it wasn’t hate.

It was math.

To my parents, love and success were a finite resource. A pie with only so many slices. If they gave any to me, that meant less for Beatrice. And that was unacceptable. Because Beatrice was the investment. The golden goose. The future of the family.

I was the spare. The backup generator in the basement. The thing you ignored until the lights went out—and then, suddenly, you needed it.

The lights had gone out.

And here I was.

I sat up slowly and turned the key halfway, enough to power the car’s electrical system. I opened the glove compartment, pushing aside napkins and expired insurance cards until I found what I was looking for: my laptop, sliding in its cheap sleeve.

My hands weren’t shaking anymore.

If they wanted me to take responsibility for “their financial problems,” then the least I could do was understand the exact size and shape of the fire they’d built around me.

I tethered my phone, stared at the screen, and logged in.

The Consumer Credit Bureau portal was familiar in a clinical way. I’d walked clients through it before—women who’d suddenly discovered that their husbands had taken out mortgages in their names, or business partners who’d only just realized their signatures had appeared on documents they’d never seen.

“Check your credit report regularly,” I always told them. “It’s basic self-defense.”

I had. Once a few years ago. Everything had been fine.

Or so I’d thought.

I typed in my Social Security number, date of birth, and the usual array of security questions. First street I lived on. Name of my elementary school. I answered them automatically, barely thinking.

Then I hit Enter.

The page took a little longer than usual to load. When it did, the blue-white light bathed the interior of my car in a strange glow.

I stopped breathing.

My credit score, once comfortably high, had dropped into the low five hundreds.

That was bad. That was very bad. But it wasn’t the number that made my stomach flip.

It was the list of open accounts.

Three credit cards. All maxed out. Total balance: around $45,000.

A business loan. Principal amount: $50,000. Status: in default.

My name was at the top of the report. My Social Security number. My address.

But I had never opened any of those accounts.

The business loan was tied to a name that made my skin go cold.

Beist Consulting LLC.

Beatrice had once launched a short-lived fashion startup under that name. I remembered the Instagram posts, the glossy shots of sample dresses and mood boards. The triumphant caption: “So excited to announce my new fashion tech venture!” It had fizzled out, like all her projects. The last post was from years ago, a blurry photo of a half-finished office space and a caption about “big things coming.”

Apparently, something had come.

Debt.

In my name.

My fingers hovered over the trackpad. Then I forced them to move, clicking on the details of the accounts one by one.

Each credit card had been opened five years earlier.

Five years ago, I’d been twenty-one, working at a grocery store, a student, still learning the basics of forensic accounting at night. I remembered the timing painfully well. I had asked my parents for help with rent that year and been told they “couldn’t afford it,” that I would have to “figure it out like an adult.”

I clicked on the contact emails and phone numbers attached to the accounts.

The recovery email was the same on every one of them.

arthur.witford@…

I leaned back in my seat as if someone had punched me in the chest.

My father.

My father had opened credit cards and a business loan in my name five years ago. He’d been using my identity as a piggy bank while I was eating toast for dinner and wrapping myself in two sweaters at night because I couldn’t afford to turn the heat up.

He’d taken my name and sold it.

I scrolled through transaction histories. Luxury stores. A travel agency. Restaurant bills that cost more than my rent. Payment to a co-working space. Payments to vendors with generic names.

My father’s email on every account.

Five years.

Five years where I could have applied for a mortgage, for a car loan, for anything—and been denied, and never understood why.

My hands settled, suddenly steady.

I waited for tears that never came.

Instead, something else rose in me—slow and cold and deliberate. The last frayed thread of loyalty snapped.

I wasn’t a daughter.

I was a resource line on a spreadsheet. A line of credit to be exploited. A social security number with a pulse.

They had watched me struggle and told themselves a story about how it was good for me. Built character. Taught independence.

All while draining me dry.

A laugh bubbled up in my throat, hysterical at the edges. I pressed my lips together hard until it died.

Okay, I thought. Okay.

They wanted to hand me a folder of crimes and send me to prison.

But they didn’t know who I was.

They didn’t know that I’d spent the last few years training to be the kind of person you absolutely should not betray on paper.

I closed the credit report tab and opened another.

If this mess with Beatrice’s company involved my name—and it clearly did, if the loan was in my Social Security—it meant I had legal access to at least part of its records. I needed those records, all of them, before they decided to destroy or “misplace” anything.

I drove across town to a place I thought of as my war room: a 24-hour co-working space in a half-renovated warehouse. It smelled like coffee and old wood and printer ink. I had a membership there under a different name—my consulting alias, which I used for private jobs and side projects.

The night manager barely looked up when I came in, just nodded and buzzed me through.

I took over my usual corner booth, plugged in the laptop, and started pulling thread after thread.

First, I accessed the public filings for Beist Consulting LLC. Anyone could get those. Ownership, registered agent, the usual. Then I used the loan information tied to my Social Security number to gain access to the business account records.

The financial statements downloaded, line after line.

I watched the progress bar fill, then opened the files.

I’m used to looking at numbers that lie. That’s the job. You scan a page that says “operating expenses,” and you learn to find the weekend in Monaco hidden inside.

But this wasn’t my usual clinical detachment. This wasn’t some faceless company swindling investors.

This was my family.

There it was: $250,000 in seed funding, raised from “angel investors.” The names were familiar—old money, new money, the extended social circle of the Sterling family. Beatrice’s future in-laws had opened doors, and she’d waltzed right through.

The money had landed in the company account like a jackpot.

Then it had bled out.

Ten thousand to a luxury travel agency. Another ten to a “creative retreat” in Bali. Five to a car dealership. Seven to a “consultant” whose address, when I cross-referenced it, turned out to be the same as Beatrice’s downtown loft. Fifteen thousand to a contractor listed under a generic name.

I checked that address too.

My parents’ house.

I sat there, in that booth, as sunrise slowly shifted the light from artificial to gray-blue, and followed the money trail. It wasn’t just Beatrice’s greed. It was systemic. A closed loop. Money from investors funneled into my sister’s lifestyle, my parents’ renovations, my father’s club dues. Once the accounts started gasping for air, my father had opened new lines of credit—in my name—so the party could continue a little longer.

They weren’t just using me as a scapegoat in the present.

They’d built this whole mess on my back years ago.

If I ran to the FBI right then, it would be… complicated. My name was all over the accounts. My Social Security number. My signature—faked, but not obviously so, not without expert analysis. My parents would claim that I had orchestrated everything, that they’d merely trusted me. The “quiet daughter” with her “computer job.” Who would a jury believe? The respectable couple with their photogenic older daughter? Or the younger one whose records made her look like she’d been secretly running a scam?

I needed leverage.

And more than that, I needed them to incriminate themselves in a way that was undeniable.

I stared at the screen, at their house’s address in the transaction logs.

The house.

If my parents had a god, it was that house.

A four-bedroom colonial in the historic district, all white columns and black shutters and painstakingly restored wood floors. They’d bought it twenty years ago, early enough that property values hadn’t yet gone insane. They’d refinanced, renovated, leveraged. Every photo Beatrice posted of “family holidays” had been taken in one of its perfectly curated rooms.

It was appraised at around $1.5 million last I’d checked.

It was also, according to the records, almost fully paid off.

They’d burned through their savings. Their investments. Their retirement accounts. Their credit. Mine.

The house was the last real thing they had.

And unlike my life, my time, my freedom—that house could be transferred, with a few signatures and the right paperwork.

I opened a new tab and navigated to the Secretary of State website for Wyoming.

Most people don’t know, or don’t care, that different states have different rules for corporate transparency. I did. Wyoming was one of those rare places that still allowed anonymous LLCs. No public membership lists. No obvious fingerprints.

I filled out the required fields with clinical efficiency, using my consulting address and a registered agent service I’d used before for a client who didn’t like her husband much. Company name: Nemesis Holdings LLC.

It was a bit dramatic, but I was past caring.

I paid the expedited fee with my own card, grimacing at the dent it made, and waited for confirmation.

When it came, I printed the formation documents, then opened a new template.

The quitclaim deed was straightforward, the kind of thing usually used when property was being transferred within a family for estate planning purposes or after a divorce. It said, in perfectly legal language, that Arthur and Martha Witford were transferring all their rights, title, and interest in the property located at [address] to Nemesis Holdings LLC, for the sum of ten dollars.

Ten dollars.

The actual number didn’t matter. The transfer did.

Once they signed it in front of a notary and it was recorded, the house would belong to Nemesis Holdings.

Nemesis Holdings belonged to me.

Of course, they would never sign that willingly.

Not unless they believed it was the only way to protect themselves.

And for that, I needed a notary I could trust. Someone discreet. Someone who wouldn’t ask unnecessary questions.

I scrolled through my contacts until I found the right name: Sarah.

I’d worked with Sarah on a handful of messy foreclosure cases. She was mobile, fast, and—most importantly—entirely uninterested in anything that wasn’t her fee and a clear set of instructions.

I dialed.

She picked up on the third ring, her voice hoarse with sleep. “Sarah Nolan.”

“Sarah, it’s Alice Morgan.”

“Alice,” she said, instantly more awake. “You don’t call unless it’s interesting.”

“It’s… sensitive,” I said. “I have a signing tonight. Private residence. My parents’. Documents are ready, but I need you to witness and notarize the deed. No questions, no chit-chat. Just IDs, signatures, stamps.”

“What time?” she asked.

“Eight p.m. sharp.”

“Same rush fee as usual?” she said.

“Double,” I replied. “And cash.”

There was a brief pause. “Done,” she said. “Text me the address.”

“Sarah,” I added before hanging up, “once the last stamp is down, I need you to leave immediately. Don’t linger, don’t accept a drink, don’t let them stall you.”

“That bad?” she asked, sounding almost amused.

“Worse,” I said. “But you don’t want to know.”

I hung up and stared at the stack of papers on the desk in front of me.

On the left: printouts of fraudulent transactions, loans, and credit cards in my name. Evidence of theft and betrayal.

On the right: the trap.

They wanted me to save them.

I was about to. Just not in the way they expected.

By the time I left the co-working space, the city was fully awake. People hurried along sidewalks with coffee cups and briefcases, unaware that somewhere above them, in a corner of a shared office, a quiet woman had just declared war on her own family.

I went home briefly, showered, and changed into the costume they expected. Plain blouse. Beige cardigan. No makeup beyond a bit of concealer under my eyes. I tucked my hair back, making myself look smaller, meek.

Then I slipped my phone into my pocket, making sure the recording app was easily accessible.

If they were going to set me on fire, I was going to make sure the flames left fingerprints.

At 7:55 p.m., I parked in front of my parents’ house.

All the lights were on. The front lawn, with its perfectly trimmed hedges and carefully placed spotlights, looked like a glossy real estate listing. Inside, I could see the chandelier in the foyer glowing warmly, the gleam of polished wood floors, the shadow of my father moving in the study.

I stood on the porch for a moment, my hand hovering over the doorbell, breathing in the familiar scent of azaleas and money.

Then I pressed the bell and, with my other hand, quietly started the recording app.

My father opened the door himself, not the housekeeper. That surprised me. He looked tired, but there was a restless energy about him, like a gambler waiting for the roulette wheel to stop.

“You’re late,” he said.

It was 7:58. I said nothing.

“Get in here,” he muttered, stepping aside.

My mother was sitting on the sofa in the study, a glass of wine in one hand. Beatrice paced the room, glancing at her phone every few seconds. Her makeup was perfect, her dress carefully chosen to look casual and expensive.

She looked up when I came in, eyes wide and red.

“Well?” my father asked. “Have you finally come to your senses?”

I set my bag down on the armchair and let my shoulders sag, letting them see what they wanted: Someone defeated. Someone scared.

“I’ll do it,” I whispered, staring at the floor.

My mother exhaled, a long, triumphant sigh of relief. “I told you,” she said to my father. “She’s a good girl deep down. She understands family.”

Beatrice made a small, hiccuping sound. “Thank you,” she breathed. “You have no idea—”

“Don’t,” I said sharply, then softened my voice. “Please. Just… don’t.”

“Fine,” my father said brusquely, as if we’d just settled who would take out the trash. “We’ll meet with the lawyer tomorrow. You’ll plead guilty, we’ll frame it as incompetence, negligence, whatever puts you in the best light while keeping Beatrice’s name out of it. We’ll figure out restitution. Most of it can be brushed under the rug if we—”

“There’s a problem,” I interrupted.

He frowned. “What problem?”

“I… spoke to someone.” I twisted my hands together, letting my voice tremble again. “A friend. A lawyer. Just hypothetically. I wanted to understand what I’m… volunteering for.”

Beatrice froze mid-pace. My mother’s fingers tightened around her wine glass.

“And?” my father demanded.

“And he said that because the fraud involves more than two hundred thousand dollars,” I said, “it’s not just prison time. The government will look for assets tied to the beneficiary of the fraud. They’ll look at the house, the renovations, the cars, the trips. Anything they can connect to the stolen money.”

I lifted my eyes and let them dart meaningfully around the room—the custom bookshelves, the antique rug, the new fireplace surround I’d seen on Beatrice’s Instagram shortly after one of the larger transfers had gone out.

“If I plead guilty,” I murmured, “they might… seize this house.”

For a second, there was nothing. No sound, no movement.

Then my father laughed.

It was short, strained. “They can’t touch the house,” he said. “It’s paid off. It’s in my name. My money.”

“Is it?” I asked softly. “Because according to the records, some of the renovations were paid for with funds from Beist Consulting. And that business loan is in my name. If the investigators connect those dots, they’ll argue the property is tainted. It’s complicated, but—”

My mother slammed her glass down so hard that red wine sloshed over the rim.

“No,” she said. “They can’t take our home.”

Beatrice’s face had gone pale beneath the makeup. “Harrison loves this house,” she whispered, as if that were the point. “His mother said it’s the only thing about our relationship she considers ‘traditional.’ If there’s some… some scandal with it…”

Her voice broke.

My father’s jaw clenched. “You’re overreacting,” he said to me. “Your ‘friend’ is fear-mongering.”

“Maybe,” I said. “Maybe I misunderstood. Maybe I’m just… scared. But what if I’m not wrong? What if, after I plead guilty, they start digging and see exactly where the stolen money went? The house is the most visible asset you have. Don’t you think they’ll look at it?”

The color began to slowly drain from his face.

Behind the professional arrogance, he wasn’t a stupid man. He knew how these things could snowball. He also knew, better than anyone, how much of this house had been funded by off-the-books money.

My father hated two things more than anything else: public humiliation and poverty.

Losing the house meant both.

“What are you suggesting?” he asked finally, voice tight.

“I thought…” I reached into my bag and pulled out the neatly clipped stack of papers, letting my hands tremble visibly. “I thought there might be a way to protect it. To keep it safe while this all… blows over. So that when I go to prison, at least you and Mom and Beatrice don’t lose everything.”

I placed the documents on his desk, close enough that he could see the heading but not far enough for him to grab easily without standing.

He didn’t.

He read the title: QUITCLAIM DEED.

His eyes narrowed. “What’s this?”

“An asset protection strategy,” I said quickly. “I set up a holding company. A sort of blind trust. Nemesis Holdings LLC. It’s completely separate from you, from me. If we transfer the house into it now, before any investigation starts, then, technically, it’s not your asset when the authorities come looking.”

I said authorities instead of “FBI” or “IRS” deliberately. It made the threat feel more vague, more overwhelming.

My mother stood and moved closer to the desk. “And who owns this… company?” she asked.

I swallowed. This was the first real test of the plan. I had to walk a razor’s edge between clever and suspicious.

“On paper?” I said. “Me. As the managing member. If your names are attached to it in any obvious way, they can trace it. They’ll freeze it. This way, the house is in a separate box, and I’m already… tainted. They won’t waste resources chasing what looks like a shell.”

My father’s eyes flicked down the page, scanning the legal language. He stopped at the signatures line and read the sentence that listed me as the sole managing member of Nemesis Holdings.

“This puts us at your mercy,” he said flatly. “You’d control the house.”

I laughed weakly. “Do I look like someone who wants control, Dad? You can force me to sign it back any time you want. I always do what you ask. I’m doing it right now.”

That was, sadly, plausible. In the story they told themselves, I was obedient, malleable. The daughter who didn’t rock the boat. The one who showed up when summoned, who said thank you for scraps.

He looked at me for a long second, searching my face for… what? Rebellion? Ego? I let him see fear.

“I don’t want you to lose this place,” I whispered. “If my going to prison can keep Beatrice out of trouble, fine. But if you lost the house on top of everything else—if the Sterlings saw a seizure notice on the front door—it would destroy her future. This way, at least, we keep something safe.”

The appeal to Beatrice’s future, to what people might think, tipped the scales.

“You’re sure this will work?” my father asked.

“No,” I said honestly. “But it gives us a better chance than doing nothing. And we have to transfer ownership before anyone starts sniffing around. Once the investigation begins, any move looks suspicious. We need to act now.”

He hesitated.

Then greed and fear joined hands, as they always did with him.

“Fine,” he said. “Call a notary. Tonight.”

“She’s already on her way,” I replied.

He blinked. “You assumed—”

“That you’d do anything to protect the house?” I said softly. “Yes. I did.”

My mother’s lips curled, but she said nothing. She wanted this over with.

At exactly eight p.m., the doorbell rang.

My father waved me out to answer it, as though I were the help. I swallowed my irritation and obeyed.

Sarah was standing on the porch, briefcase in hand. She wore dark jeans and a blazer, her hair pulled into a no-nonsense braid. Her gaze flicked over me, then over my shoulder into the house.

“Ms. Morgan,” she said.

“Thank you for coming,” I said. “It’ll be quick.”

I led her to the study.

“This is Sarah, the notary,” I announced.

Sarah set her briefcase down and pulled out her seal, her ledger, and a set of pens. “Whose signatures am I notarizing?” she asked briskly.

“Mine and my wife’s,” my father replied. “Arthur and Martha Witford.”

Sarah nodded. “I’ll need to see your IDs.”

They produced their driver’s licenses. She examined them, recorded the details. “And this is the document?” she asked, tapping the quitclaim deed.

“Yes,” my father said impatiently. “Transferring property to a holding company. Estate planning. We’re in a rush.”

Sarah’s expression didn’t flicker. If she suspected anything, she didn’t show it.

“Sign here,” she said, pointing. “And here. And initial on each page.”

They signed.

Their names flowed onto the paper in familiar, looping strokes.

Sarah notarized each signature, her stamp pressing down with satisfying finality. The sound was almost a drumbeat.

“That’s it?” my mother asked, a little breathless.

“That’s it,” Sarah said, packing her things. “You keep that copy. I assume Ms. Morgan will take the original for recording?”

“Yes,” I said. “I’ll handle the filing.”

My father nodded absently, already looking relieved.

I walked Sarah to the door, pressing an envelope of cash into her hand on the porch.

“Thank you,” I said.

She weighed it briefly, then slipped it into her pocket. “You know this kind of rush work usually means trouble,” she murmured.

“Usually,” I agreed.

She studied my face for a second. Something softened in her eyes. “Be careful,” she said quietly.

“I am,” I replied.

She left.

When I returned to the study, my parents were already relaxing, the tension bleeding out of their shoulders. My mother had refilled her wineglass. Beatrice had sunk onto the sofa, scrolling through her phone, no doubt updating some group chat about how “crisis management” was underway.

“You were… useful for once,” my father said, sitting back in his leather chair.

My mother gave me a thin smile. “See? You can contribute when it really matters. Stop crying now. You know your place, Alice. Beatrice is the flower. You’re the dirt. Your job is to bury yourself so she can bloom.”

Beatrice flinched slightly at that phrasing, but she didn’t protest.

“Tomorrow,” my mother continued, using the tone she reserved for grocery lists and charity events, “you’ll go to the lawyer’s office with your father. You’ll say you did it. That you mismanaged things. That you panicked and lied. You’ll accept whatever deal they recommend. We have a wedding to plan. There’s no time for drama.”

The dirt comment rang in my ears like a bell.

They’d always thought of me that way. As the background. The scenery. Something to be walked on, shaped, used.

I straightened slowly.

“About that,” I said.

My father frowned. “About what?”

“Tomorrow,” I said. My voice was no longer trembling. It was clear. Calm.

“I’m not going to the lawyer’s office.”

For a second, no one reacted. Then my father barked a laugh.

“Don’t start getting brave now,” he said. “You already signed up for this. We have a plan, and you’re the centerpiece.”

“No,” I said. “I’m not.”

I reached into my pocket, picked up my phone, and turned the screen toward them.

The recording app was still running. The red timer clearly showed the duration of the audio.

“What is that?” my mother asked sharply.

“Insurance,” I said. “I started recording when I rang the doorbell. It’s picked up everything. The part where you asked me to take the fall. The part where you admitted to using stolen funds for the house. The part where you called me dirt and said my job was to bury myself so Beatrice could bloom.”

My father lurched to his feet, his face turning an alarming shade of red. “Turn that off,” he snarled. “You don’t record your own family. Have you lost your mind?”

“I’m turning it off now,” I said, carefully tapping the screen. “But it’s already saved. And backed up to the cloud. Multiple places, actually.”

They stared at me.

The balance in the room shifted, almost imperceptibly.

“I’m not going to the police,” I said. “Not yet. And neither are you.”

My father’s eyes narrowed. “You think you’re in a position to make demands?” he said. “Those accounts. Those loans. They’re in your name. If anyone looks, they’ll see you.”

“True,” I said. “But they’ll also see the money trail. Beist Consulting’s funds going straight into your renovations, your club dues, your vacations. They’ll see the business loan in my name that I never applied for, tied to your email address for recovery. They’ll see a neat pattern: money in from investors and the government, money out to Beatrice and to you.”

“You can’t prove we knew,” my mother said quickly, her voice a little higher than usual. “You could have done all of that. You work with numbers. You’re… clever.”

“That’s where this comes in,” I said, lifting my phone slightly. “You just spent the last half hour discussing how I’m going to prison so Beatrice doesn’t have to. How you used the money to pay for things. How you needed me to ‘take the fall’ because it would ruin her life if she were caught. That’s called… what’s the phrase? Oh, right. Consciousness of guilt.”

My father swallowed. His Adam’s apple bobbed.

“Even if we didn’t go criminal,” I continued, “this recording would be miraculous in civil court. Any attempt on your part to sue me for the house, for example, would be laughed out of existence because of something called the ‘unclean hands’ doctrine. You can’t go into court asking for justice when you’ve just admitted, on tape, that you committed fraud.”

My father sank back into his chair slowly.

“What did you do?” he whispered.

“I protected myself,” I said. “And I took ownership of what I’m owed.”

My mother’s eyes narrowed. “This house is ours.”

“Not anymore,” I said. “You just signed it over to Nemesis Holdings. An entity I control completely. No side agreements. No co-owners. No rights for you. You are, legally speaking, tenants here now. At best.”

“You tricked us,” my mother hissed.

“Yes,” I said. “I did. The same way you tricked me, five years ago, by opening lines of credit in my name. The same way you tried to trick the IRS, and your investors, and the government. Consider this… a rebalancing.”

Beatrice finally spoke, her voice shaking. “You can’t do this,” she said. “You’re my sister. You’re supposed to help me. Harrison—”

“Harrison,” I said, “deserves to know he’s marrying someone who thinks other people’s freedom is an acceptable wedding gift.”

Her face crumpled. “You wouldn’t,” she whispered.

“I sent myself an email draft earlier,” I said. “Addressed to him and his parents. It contains a summary of what I’ve found so far, the most damning transaction records, and a copy of the audio file. All I have to do is hit send.”

“You’re bluffing,” my father said. “You don’t have the guts—”

I opened my phone, tapped the mail app, and showed him the draft, already addressed, the attachments clearly visible.

He shut his mouth.

“Here’s how this is going to work,” I said calmly. “You will not contact the police. You will not contact any investigators. You will not try to throw me under the bus. You will not attempt to reverse the deed you just signed. You will not, in any way, try to force me to fix this for you or take responsibility for your crimes.”

“And if we do?” my mother asked, folding her arms.

“Then the recording goes to the FBI and to the Sterlings,” I said simply. “Along with every file I’ve pulled from Beist Consulting, every fraudulent loan in my name, every email linking your accounts to mine. I will walk into their office with a thumb drive and a printed summary, and I will tell them everything. It won’t keep me completely safe. I’m prepared for that. But it will drag you down with me, and you will lose much more than I do.”

“You wouldn’t destroy your own parents,” my father said softly.

I held his gaze. “You already destroyed your daughter,” I said. “This is just me declining to go quietly.”

The room was very quiet.

For the first time in my life, they were the ones without a script.

“You… you can’t throw us out,” my mother said finally, grasping at a new argument. “We’ve lived here for twenty years. We raised you here. This is our home.”

“I know,” I said. “Which is why I’m giving you more mercy than you ever gave me.”

I reached into my bag again and pulled out a letter I’d drafted at the co-working space. The words “Notice to Vacate” were clearly visible at the top.

“You have seven days,” I said, placing the paper on the desk where my father had laid the prison folder earlier. “To leave. Take whatever you can. Sell what you can. But in seven days, if you are still here, I will start formal eviction proceedings. I’ll also file to record the deed with the county. Once that’s done, this house is mine, and you are, in the eyes of the law, squatters.”

“You can’t be serious,” my mother whispered.

“I am,” I said. “Very.”

Beatrice stared at me, tears gathered in her eyes but not falling. “What am I supposed to do?” she asked. “Where am I supposed to go?”

I thought of all the nights I’d spent in my freezing studio, wrapped in a thrift-store blanket because my parents had said things were “tight” while my father was applying for another card in my name.

“Figure it out,” I said. “Like an adult.”

My father’s voice dropped to a desperate whisper. “We’ll… we’ll make this right,” he said. “We’ll sign it back. We’ll… we’ll give you something. Just not the house. Anything but the house.”

I smiled, a small, humorless curve of my lips.

“Dad,” I said. “I don’t trust you to give me a glass of water, much less a house. I’m not bargaining. I’m informing you.”

I picked up the folder they’d given me earlier, the one filled with Beatrice’s crimes, and tucked it under my arm. Not because I needed it—I already had digital copies of everything—but because it felt symbolically satisfying.

“You said two years in prison wouldn’t kill me,” I said, turning toward the door. “Losing this house won’t kill you either. But it might finally teach you what consequences feel like.”

I walked out.

They didn’t call me back this time.

The next seven days were… strange.

They called, of course. At first my father demanded, then he threatened, then he tried bargaining. My mother’s voicemails swung wildly between pleading and icy fury. Beatrice texted long paragraphs about sisterhood, about how “families forgive,” about how Harrison’s mother would “never understand this sort of drama.”

I didn’t respond.

I recorded every voicemail, saved every message, backed up every file.

On the fifth day, my father left a particularly venomous message about disowning me. It would have stung, once.

Now it just made it very clear that we were, finally, being honest about what we were to each other.

On the seventh day, a moving truck appeared in front of the house.

I sat in my car across the street, watching from a shadowed spot like it was a show I hadn’t purchased tickets for but somehow still deserved to see.

Beatrice stormed in and out, carrying boxes that were more designer clothes than necessities. My mother supervised the wrapping of furniture with grim determination, her mouth a thin line. My father directed movers, his shoulders stooped in a way I’d never seen before.

At one point, he stopped at the front gate, his hand resting on the iron post, and looked back at the house with an expression that almost made me feel something like sympathy.

Almost.

Then I remembered my credit score. The default notices in my name. The cold way he’d said, “We’ll pay you when you get out,” as if my freedom were a loan he was offering.

The sympathy evaporated.

When the truck finally pulled away, the house looked oddly… smaller. Empty windows. Dark rooms. Just a building again, stripped of its performance.

I waited two more hours, then walked up the path and slid my new keys into the front door.

The air inside smelled different already. Less like my mother’s perfume and more like dust and furniture polish. There were faint rectangles on the walls where paintings had hung, lighter patches of carpet where heavy furniture used to be.

I walked from room to room slowly, my footsteps echoing.

In the kitchen, the marble countertops gleamed. In the dining room, the heavy table was gone, leaving only indentations in the rug. In the study—the room where my father had offered me prison like a favor—the desk still stood, bare now, the leather chair pushed back slightly as if he’d just stood up and walked away.

I ran my hand along the edge of the desk, feeling the grooves in the wood.

“This is mine,” I said quietly.

Not the house, exactly.

The choice.

For the first time in my life, I held something my parents couldn’t take from me.

Three months later, I sat in that same study, my laptop open, sunlight streaming in through the tall windows.

The deed had been recorded. My name—and Nemesis Holdings—were on file with the county. Property taxes, utilities, insurance: all paid from an account with my name on it, funded not by fraud but by my own salary.

I’d kept my job, after some careful conversations with the partners at my firm. I’d given them a sanitized version of events: discovered identity theft, quietly rectified it, took a hard line with the offenders. I didn’t mention the house. They didn’t ask for details. They knew enough about the kinds of clients we dealt with to fill in some blanks.

I’d hired a lawyer of my own, one I trusted, to start the slow process of unwinding the fraudulent accounts in my name. It would take time, affidavits, perhaps litigation. But I had documentation. I had recordings. I had a paper trail a mile long.

I had leverage.

Word, inevitably, had spread in our parents’ social circle.

They were no longer at the country club. Their membership, quietly unpaid, had lapsed. My mother’s charity board appearances had dwindled. Beatrice’s Instagram had gone quiet for a while, then returned with a slightly more muted tone—photos of “fresh starts,” “new beginnings,” “embracing simplicity.”

I knew, from a mutual acquaintance who loved gossip, that Harrison’s parents had “postponed” the wedding indefinitely. The official story was that they were “taking time to focus on themselves as a couple.”

The unofficial story was that the Sterlings had discovered “financial irregularities” and decided their son’s future was better protected elsewhere.

I didn’t send them anything.

I hadn’t needed to.

My parents had always believed that flowers needed dirt to grow.

They just forgot that the dirt is what everything stands on. That it can shift. That it can, if pushed long enough, become a landslide.

I leaned back in my chair, listening to the quiet creak of the old house settling around me.

Was I happy?

Not exactly. Happiness is too simple a word for the complicated tangle of guilt, relief, anger, and grim satisfaction I felt.

I missed, sometimes, the fantasy I’d clung to for years—the idea that if I just worked a little harder, if I were a little more helpful, a little less demanding, they would finally see me. Love me. Choose me, for once.

That fantasy was dead now.

What I had instead was reality.

A stable career. A roof over my head. A house that echoed with my own footsteps, where every decision—from what color to paint the walls to whether to invite anyone over—was mine.

I had nights where I woke up at 3 a.m., heart pounding, certain that someone was going to knock on the door and drag me away. Trauma doesn’t evaporate because you’ve won a single battle.

But I also had mornings where I made coffee in my kitchen, barefoot on the cool tile, and realized I wasn’t waiting for the other shoe to drop anymore.

The other shoe had dropped.

On them.

My phone buzzed on the desk.

A text from an unknown number.

We’re staying at your aunt’s. She won’t take our calls anymore either. Money’s gone. You took everything.

No name, but I knew the voice.

My mother.

I stared at the message for a long time.

Then I typed a reply.

You took from me first.

I hovered over the send button.

After a moment, I deleted the words.

No reply was an answer too.

I put the phone face down and looked around the study. My study now. I’d begun replacing things slowly. The heavy oil paintings had been taken down, replaced with shelves of books I actually wanted to read. The massive globe my father liked to spin while pontificating was gone, donated to a thrift store. The desk remained, but I’d swapped the imposing leather chair for one that didn’t make me feel like I was sitting in someone else’s throne.

The window overlooked the street. The same street where, months earlier, I’d watched a moving truck carry away the last pieces of my childhood.

A breeze stirred the curtains.

I exhaled.

People like my parents think they are untouchable, that the rules are for other people, that there will always be someone out of frame willing to fall on the sword for them.

For twenty-six years, I’d been that someone.

Not anymore.

They were right about one thing: I was the dirt.

But they forgot that without the ground, there is nowhere for anyone to stand.

And now, for the first time, I stood on my own.

THE END.