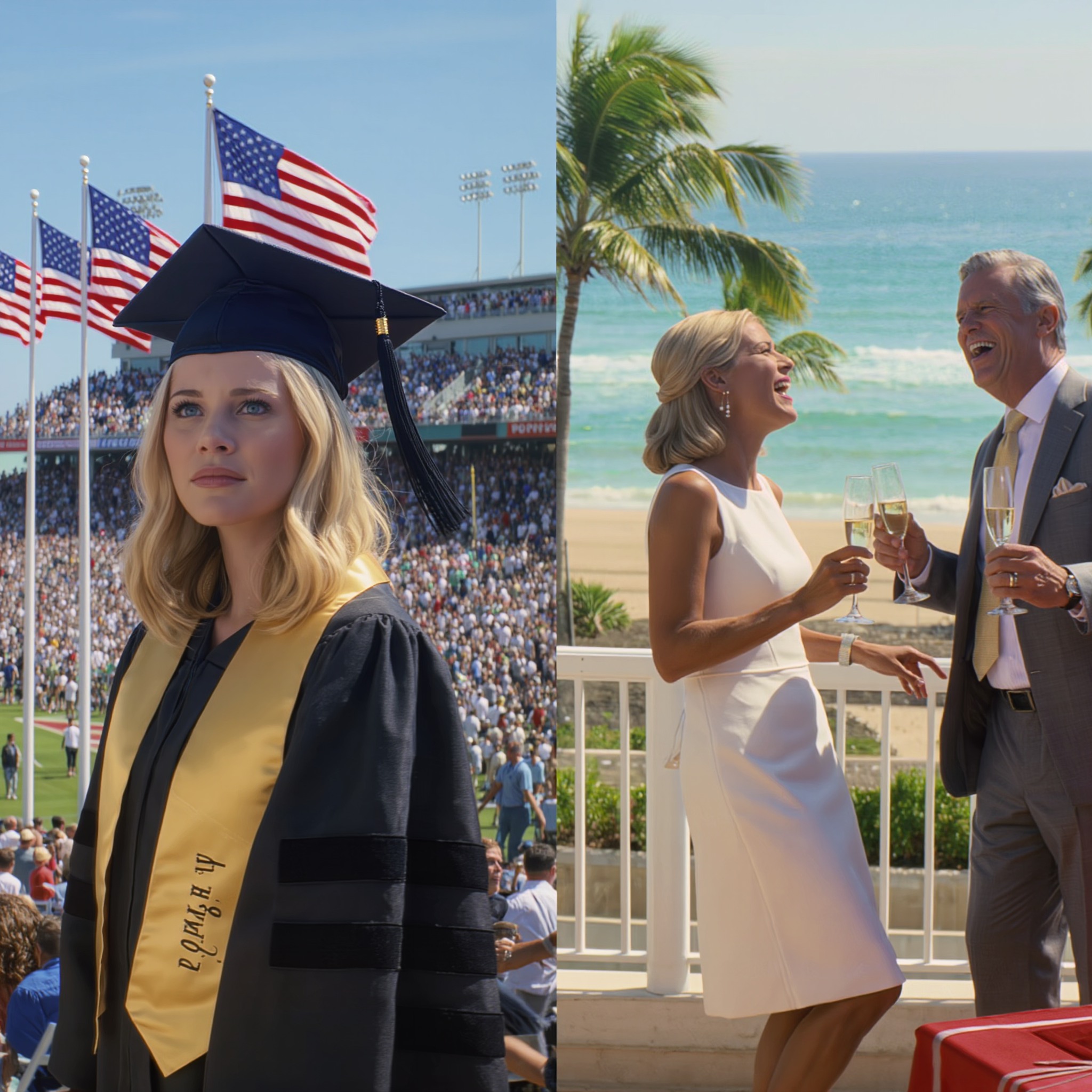

I did not shed a tear when my mother said they would miss my graduation for a resort trip with my sister. I simply asked if they preferred the live stream link or photos later. My father asked if I understood, and I said I did because I understood. I altered one line on the university paperwork. By the time the announcer invited my parents to stand, my folks were holding cocktails three hundred meters away. They dropped them.

My name is Aurora Hill. I am twenty-three years old, and until last Tuesday, I was the daughter of Robert and Linda Hill. I suppose biologically I still am, but biology is a weak tether when the emotional line has been severed with a pair of rusty shears. I live in a town called Marlin Bay, a place that looks beautiful on postcards but feels suffocating when you are the one trying to breathe inside of it. I attend, or rather I am about to graduate from, Lake View State University. The degree I earned there is in communications, but my real education came from the eight minutes and forty-five seconds I spent on the phone with my parents three days before the ceremony.

The kitchen of my small apartment was quiet. The refrigerator hummed its low electric drone, a sound that usually faded into the background, but in that moment felt deafening. My phone sat on the laminate counter, speaker on, vibrating slightly with the resonance of my mother’s voice.

“Aurora, honey, you know how proud we are,” she said. Her voice had that specific pitch she used when she was asking for a favor that was actually a demand. It was a soft, breathy tone designed to make you feel guilty for even thinking about saying no. “It is just that Sloan is in a really bad place right now. A really dark place.”

Sloan is my older sister. Sloan is always in a place. Usually, that place is the center of the universe, but currently, it was apparently a dark pit of despair because her on-again, off-again boyfriend had broken up with her for the fourth time in two years.

“We understand that graduation is a big milestone,” my father chimed in. His voice was deeper, more pragmatic—the voice of a man who believed he was negotiating a business deal rather than cancelling on his youngest daughter. “But we found this last-minute package for the Sapphire Coast Resort. It is an all-inclusive wellness retreat. The therapist recommended a change of scenery for your sister immediately. We leave tomorrow morning.”

I stood there staring at a stain on the linoleum floor. It looked like a map of a country that did not exist. I waited for the punchline. I waited for them to say that they would fly back for the ceremony, or that Dad would stay behind while Mom took Sloan. I waited for the negotiation.

“The ceremony is on Saturday,” I said. My voice sounded flat, unrecognizable to my own ears. “That is in three days.”

“We know, sweetheart,” Mom said, and I could hear the rustle of packing tissue in the background. She was already folding clothes. She was already gone. “But the flight schedules just do not align. If we do not take this booking now, we lose the deposit. And you know how expensive these places are. We are talking two thousand dollars just to hold the suite. We cannot just throw two thousand dollars away.”

They could not throw two thousand dollars away on a deposit, but they could throw away four years of my life. I had worked two jobs to pay my tuition. I had taken the early morning shifts at the campus coffee shop and the late-night shifts at the library. I had applied for every grant, every scholarship, every financial aid opportunity available at Lake View State. I had done it so I would not be a burden. I had done it so they could focus on Sloan. And now, at the finish line, the burden was not the money. The burden was my presence.

“So you are not coming.” I stated it; it was not a question.

“It is not that we do not want to,” Dad said, a hint of impatience creeping in now. He hated when I made things difficult. He hated when I did not play the role of the easy child. “It is a crisis. Aurora, your sister’s mental health is a priority. You are strong. You have always been the independent one. We know you understand.”

I did understand. That was the problem. I understood perfectly. I understood that in the hierarchy of the Hill family, Sloan’s whims were emergencies and my achievements were inconveniences. I understood that my graduation was merely a calendar notification they could swipe away to make room for a spa weekend. I did not cry. That surprised me. I expected the sting of tears, the lump in the throat, the desperate plea for them to love me enough to show up. But there was nothing, just a cold spreading numbness, like I had been injected with local anesthetic.

“Okay,” I said.

The silence on the other end was heavy. They were waiting for the fight. They were prepared for the guilt trip, armed with their rehearsed defenses about family unity and compassion. They did not know what to do with “okay.”

“Okay?” Mom asked, hesitant.

“Yes,” I said. “I understand. The resort sounds lovely. I hope Sloan feels better.” I paused, and then I asked the question that sealed the coffin on my childhood. “Do you want me to send you the link for the live stream, or should I just send photos after it is over?”

“Oh,” Mom said. She sounded relieved but also slightly confused. The script had changed and she had lost her place. “The live stream would be great. We can watch it from the hotel room. Maybe order room service. We will make a toast to you.”

“Right,” I said. “A toast. Have a safe flight.”

“We love you, Aurora,” Dad said, the words automatic. A sign-off like Sincerely at the bottom of a form letter. “We will make it up to you.”

“I know,” I said. I hung up.

The kitchen was silent again. The fridge hummed. I walked over to the closet in the hallway and opened the door. Hanging there, still wrapped in its protective plastic, was my graduation gown. It was black with a gold sash that signified I was graduating with honors. I had paid fifty-five dollars for the rental fee. I had paid one hundred and twenty dollars for the cap and tassel. I had bought a new dress to wear underneath, a modest navy blue sheath I found on the sale rack for thirty dollars. I reached out and touched the plastic. It crinkled under my fingers.

I had spent my entire life waiting for them to arrive. I had looked for them in the stands at my middle school piano recital only to see empty chairs because Sloan had a dance competition. I had scanned the crowd at my high school debate finals, only to find them missing because Sloan had needed help moving into her third apartment that year. I had spent twenty-three years auditing my own needs, shrinking myself down so I would be portable, easy to handle, low-maintenance. I thought if I required less, they would have more to give. I was wrong. You cannot bank love. You cannot save it up by not spending it. If you do not demand your space, people will simply expand into it until you cease to exist.

I walked into my bedroom and sat down at my desk. My laptop was open, the screensaver drifting with generic geometric shapes. I woke the computer up. There was an email in my inbox from the Lake View State University commencement committee. The subject line read: Urgent: Final confirmation of guest list and acknowledgements. I had opened it yesterday but hadn’t filled it out yet. I had been waiting to confirm if Dad could get the Friday off work so they could drive down early. I clicked the link. The form loaded, a sterile white page with the university crest at the top. I scrolled down past the sections about dietary restrictions and handicap accessibility. I stopped at the section titled Family Supporters to be Acknowledged.

The text below the header read: Lake View State University prides itself on community. As part of this year’s ceremony for students graduating with honors, we will be projecting the names of your primary supporters on the main screen behind you as you walk the stage. Please list the names of the parents, guardians, or spouses who have made this journey possible.

My fingers hovered over the keyboard. The blinking cursor waited in the box labeled Name One. Reflex. That was what it was. My muscle memory wanted to type Robert Hill. It was what I was supposed to do. It was the social contract: You graduate, you thank your parents, you take the picture, you pretend everything is fine. If I typed their names, they would see it on the live stream in their resort room. They would raise their cocktail glasses. They would say, “See, she is fine. She appreciates us.” They would get the credit for the woman I had become despite the fact that they had been absent for the construction.

I thought about the resort. I imagined Sloan lying on a massage table, complaining about her ex-boyfriend while the ocean breeze drifted through the window. I imagined my parents nodding sympathetically, paying the bill, feeling good about being such supportive parents to a child in crisis. They were three hundred meters away. They had chosen the sand over the stage.

I looked at the empty box. I did not feel angry. Anger is hot. Anger is messy. This was something else. This was clarity. It was sharp and cold, like inhaling icy air in the middle of winter. I realized then that I had a choice. I could continue to protect their image, to be the shadow that made their light look brighter. Or I could simply tell the truth. Not a shouted truth, not a dramatic accusatory truth, just the factual reality of who was actually there. Who had asked me if I was okay? Not on the big days, but on the Tuesday nights when I was drowning in coursework. Who had brought me soup when I had the flu sophomore year and my mother had just told me to sleep it off over text message? Who had read my thesis draft at two in the morning because I was panicking about a comma splice?

It wasn’t Robert and Linda Hill.

My fingers moved. I did not type my father’s name. I did not type my mother’s name. I typed the name of the woman who had let me sleep on her couch for a week when my dorm room flooded and my parents said they couldn’t wire me money for a hotel because they were remodeling the kitchen. I typed the name of the man who had sat with me in the hospital waiting room when I broke my wrist while my parents were on a cruise. I typed the name of the professor who told me I was a writer when my father told me I should be a dental hygienist because it was safer. I filled the three slots: Tracy Simmons. Darnell Simmons. Dr. Evan Hart.

I stared at the names. They looked right. They looked solid. I scrolled down to the bottom of the page. There was a checkbox: I confirm that the information provided is accurate and may be used for public broadcast during the ceremony. I clicked the box. A warning popup appeared: Please note, once submitted, these details cannot be changed after midnight tonight due to production schedules for the stage display.

I checked the time. It was 11:45 at night. I had fifteen minutes to change my mind. I had fifteen minutes to be the good daughter, the invisible daughter, the daughter who accepts the scraps and calls it a feast.

My phone buzzed again. A text from my mother. Just landed the confirmation email for the resort. So relieved. We will make it up to you. Honey, send us a pic of the gown.

She wanted a picture of the gown. She wanted the prop without the performance. I looked at the text. Then I looked back at the screen.

“No,” I whispered to the empty room. “You don’t get the picture.”

I moved the mouse to the submit button. I did not click it with rage. I clicked it with the gentle precision of a surgeon making an incision. Your response has been recorded. The screen went white, then returned to the university homepage. It was done. I sat back in my chair and exhaled for the first time all day. The air reached the bottom of my lungs. I felt lighter. I felt terrifyingly, wonderfully unburdened. They had made their reservation. Now I had made mine.

They thought their absence would be a quiet thing, a gap I would cover up with polite excuses and forced smiles. They thought I would tell people, “Oh, my parents are so sick. They are heartbroken they couldn’t make it.” They counted on my silence. They leveraged my dignity against their selfishness. But silence is a funny thing. If you hold it long enough, it stops being a shield and starts being a weapon.

I stood up and walked back to the kitchen. I made myself a cup of tea. I did not turn on the lights. I stood in the dark, watching the streetlights flicker on the pavement outside. If they chose to be absent, if they chose the resort and the cocktails and the coddling of my sister over the culmination of my four years of hard labor, then so be it. I would not scream at them. I would not beg them to come back. I would simply let the day unfold. I would let the giant screen behind the stage tell the story. I would let the announcer read the names I had provided. I took a sip of tea. It was hot, bitter, and grounding. Let them have their view of the ocean. On Saturday, the view from the stage would be entirely different.

And for the first time in my life, I wasn’t going to edit the footage.

To understand why I deleted my parents’ names from a digital form, you have to understand the house I grew up in. If you walked into the Hill residence on a Sunday afternoon, you would see a masterpiece of suburban tranquility. My mother, Linda, has a talent for staging. There are always fresh hydrangeas in the vase on the entryway console. The throw pillows are always fluffed to a perfect forty-five-degree angle. During the holidays, the garland is draped with the precision of a mathematically calculated curve. It is a home that screams warmth, family, and togetherness. But if you look closer, specifically at the gallery wall leading up the staircase, you begin to see the architecture of our family’s soul.

There are photos of Sloan winning the regional dance competition. There are photos of Sloan as prom queen wearing a tiara that cost a hundred and fifty dollars. There are photos of Sloan standing next to a minor celebrity at a music festival. And then there are the group shots where I am present, usually in the back row, usually slightly out of focus. There are no solo portraits of me after the age of ten. That was the year Sloan entered middle school and developed anxiety, and the gravitational pull of the household shifted permanently to her orbit. In the solar system of our family, Sloan is the sun. She burns bright. She is volatile and she demands that every other celestial body revolve around her to keep her warm. My parents are the planets locked in a desperate, dizzying rotation, terrified that if they stop spinning, the sun might burn out. And me? I am not even a planet. I am a shadow. I am the dark space between the stars that knows how to make itself small so the light has more room to shine.

We have a tradition of Sunday dinners. My mother makes a roast, my father opens a bottle of red wine, and we sit at the mahogany table to perform the ritual of being a family. For the last four years, these dinners have followed an identical script. Sloan talks. She talks about her job as a social media coordinator, a job my father helped her get by calling a golf buddy. She talks about the coworker who looked at her the wrong way, which usually spirals into a twenty-minute monologue about how jealous women are of her. She talks about her latest romantic entanglement, describing the text messages in forensic detail.

“He said he was going to call at eight, but he didn’t call until eight-thirty,” Sloan would say, stabbing a roasted potato with her fork. “Do you think that means he is seeing someone else? I feel like my chest is tightening. Mom, my chest is tightening.”

And my parents would lean in. Their food would go cold. My mother would reach across the table to stroke Sloan’s hand. My father would put down his wine glass and offer strategic advice on how to handle a man who calls thirty minutes late. They were engaged. They were present. They were terrified of her unhappiness.

I would sit there eating in silence, waiting for the pause. When the pause finally came, usually while Sloan was chewing, I would try to offer a piece of my life.

“I got accepted into the honor society,” I said once during my sophomore year.

My mother glanced at me, her eyes still glazed over with worry for Sloan. “That is nice, Aurora. Pass the butter, please.”

“It is a big deal,” I tried again. “Only the top five percent of the class gets in.”

“We know you are smart, honey,” my father said, already looking back at Sloan. “Sloan, did you reply to him?”

That was the refrain of my life: We know you are smart. It sounded like a compliment. But in the Hill household, it was a dismissal. It was code for: You do not need us. You are functional. You are the low-maintenance model. So, please stop asking for maintenance.

I learned early on that being independent was not a personality trait I was born with. It was a survival mechanism I was forced to develop. When I was nineteen, the alternator on my used sedan died in the parking lot of the grocery store. The repair was going to cost four hundred dollars. I had three hundred dollars in my bank account. I called my father.

“Dad, I’m stuck at the shop,” I said. “The car won’t start. The mechanic says it is the alternator.”

“Oh, Aurora,” he sighed. I could hear the television in the background. “I am right in the middle of helping Sloan move her furniture. She decided she hates the layout of her apartment again. Can you figure it out? Call AAA. You have your own membership, right?”

“I don’t have the money for the repair,” I said, hating the way my voice wobbled.

“You are good with money,” he said distractedly. “Put it on a credit card. You can pick up a few extra shifts. You always figure it out. You are the resourceful one.”

I slept in my car that night because I couldn’t afford the tow truck and the repair until I got paid on Friday. I walked three miles to work for the next four days. When I finally saw my parents again, they didn’t even ask how I got home. They just praised me for handling business like an adult. They loved my independence because it was free. It cost them nothing—no time, no emotional energy, and certainly no money.

Sloan’s crises, on the other hand, were expensive. I watched them funnel thousands of dollars into her wellness. There were yoga retreats in Arizona when she felt spiritually lost. There were new wardrobes when she felt her image was stale. There was the time they paid off her credit card debt because the stress of owing money was making her break out in hives. Meanwhile, I was the one filling out financial aid forms until my eyes burned.

I remember one specific afternoon in the kitchen just before my junior year. I had my tuition bill spread out on the counter. The university had raised the fees for lab materials. Even with my scholarship and my job at the library, I was short by six hundred dollars for my textbooks. My mother was at the stove making herbal tea for Sloan, who was lying on the sofa in the next room recovering from a migraine induced by a bad haircut.

“Mom,” I said, keeping my voice low. “I need to talk to you about my books for next semester.”

She didn’t turn around. “Can it wait, Aurora? The kettle is about to whistle.”

“It is due tomorrow,” I said. “I just need a loan, six hundred dollars. I will pay you back fifty dollars a week from my paycheck.”

She turned then, holding the steaming mug. She looked at me with a weary, almost disappointed expression. “Aurora, we just had to put down a deposit for Sloan’s new apartment. The security deposit was first and last month’s rent. Cash is a little tight right now.”

“It is for school,” I said. “It is not for a purse. It is for textbooks.”

“I know,” she said, softening her voice to that pitying tone that I hated more than her anger. “But you are so clever. Can’t you find them used online or borrow them from the library? You always find a way. You are the strong one.”

The strong one. That was the label they slapped on my neglect to make it look like a trophy. I didn’t argue. I sold my flute. The flute I had played for six years in the school band. I took it to a pawn shop downtown and sold it for four hundred and fifty dollars, and I made up the rest by skipping lunch for a month. When I told them I sold it, my father just nodded and said, “Well, you weren’t playing it much anyway, were you? Smart move.”

But the money wasn’t the worst part. The money was just math. The worst part was the way they treated the things that actually mattered to me. I am a writer. It is the only place where I feel loud. I write essays, short stories, observational pieces about the strange, quiet corners of human interaction. When I was twenty-one, I had a piece published in a legitimate literary journal. It was a creative non-fiction story about growing up in a small town. I was so proud. I bought three copies. I left one on the kitchen counter with a sticky note that said, Page 45.

Two days later, we were all in the living room. Sloan picked up the journal. She didn’t read it silently. She read it out loud using a dramatic, mocking voice, pausing to roll her eyes at the emotional parts. The silence in the house was heavy, like a wet wool blanket. She read, snickering.

“Oh my god, Aurora, this is so angsty. Who talks like a wet wool blanket? You are so dramatic.”

I looked at my parents. I waited for them to say, Stop it, Sloan. It is beautiful. She got published. Instead, my father chuckled. “It is a bit heavy, isn’t it, honey? You were always such a serious child.”

“It is just a story,” I said, snatching the journal from Sloan’s hand.

“Don’t be so sensitive,” my mother chided, not looking up from her iPad. “Your sister is just teasing. You know she is proud of you. She’s just having fun. You don’t need to be so defensive all the time. It makes you hard to be around.”

Hard to be around. That phrase stuck in my throat like a fishbone. I was hard to be around because I had boundaries. I was hard to be around because I didn’t laugh when they mocked my soul. Sloan could scream, throw vases, and demand the world, and she was “passionate and fragile.” I defended my art for ten seconds, and I was “difficult.”

I realized then that they didn’t hate me. Hate would have been active. Hate would have required passion. This was something far more eroding. They were indifferent to me. They viewed me as a piece of furniture that had suddenly started speaking, and they found it annoying. They had convinced themselves that I didn’t need their attention. They told their friends, “Aurora is so low-maintenance. She is a dream.” They used my resilience as an excuse for their laziness.

I remember my twenty-second birthday. I had booked a table at a small Italian restaurant for the four of us. It was the one thing I asked for that year. Two days before the dinner, my mother called.

“Aurora, honey,” she started. I knew the tone. “Sloan has a callback for a commercial in the city on your birthday. She is really nervous. We need to drive her up there and support her. Can we move your birthday dinner to next week? Maybe a Tuesday?”

“My birthday is on Saturday,” I said.

“I know, but we are celebrating the person, not the date, right?” She laughed, a nervous tinkling sound. “You are an adult. You understand. Sloan needs us right now.”

I cancelled the dinner. I didn’t reschedule it. On my birthday, I sat alone in my apartment and ate takeout sushi. They sent a text: Happy birthday. So proud of our big girl. Rain check on dinner.

The rain check never came. They forgot about it by Monday because Sloan didn’t get the commercial and needed retail therapy to cope with the rejection.

So, when the phone call came about the resort, when they told me they were skipping my graduation, it wasn’t a shock. It was a logical conclusion. It was the season finale of a show I had been watching for twenty-three years. Of course they were going to the resort. Of course Sloan’s stress was more important than my four years of academic excellence. Of course I was expected to understand.

I stood in the center of my bedroom looking at the family photo I still kept on my dresser. It was taken five years ago. Sloan is in the middle, beaming, her arms linked through my parents. I am standing slightly to the left, a polite distance away, smiling a smile that doesn’t reach my eyes. I picked up the frame. I looked at the glass. I realized that I wasn’t angry at them for leaving. I was angry at myself for staying. I was angry that I had spent so long trying to audit my own needs to fit into their budget only to realize they never intended to buy what I was selling.

I didn’t want to scream at them. I didn’t want to key their car or burn the house down. That is what Sloan would do. That is what a “passionate” person would do. I just wanted them to see the reality they had created. I wanted them to look at the stage and see the empty space where their support should have been. I wanted to strip away the Aurora is fine narrative and force them to look at the raw data. I wasn’t looking for revenge. Revenge is about hurting someone else. This was about saving myself. It was about walking out of the shadow and for the first time refusing to dim my own light just so they wouldn’t have to squint.

I placed the photo face down on the dresser. The silence in my room didn’t feel like a wet wool blanket anymore. It felt like armor. I checked my watch. It was past midnight. The form was locked. The names were set. In three days, I would walk across a stage. In three days, they would be sipping mimosas by a pool, confident that their independent daughter was handling things just fine. And I was. I was handling things exactly the way they taught me: by doing it without them. But this time, I wasn’t going to hide the evidence. This time the shadow was going to cast a shape so distinct, so undeniable, that even they wouldn’t be able to look away.

The suspicion did not hit me all at once. It crept in slowly, like a draft under a door frame you thought was sealed shut. After I submitted the form, removing my parents from the ceremony acknowledgement, I sat in the darkness of my apartment and let my mind wander back to the events of the last forty-eight hours. Something about the timeline felt disjointed. My parents were impulsive when it came to Sloan, yes, but they were also creatures of financial anxiety. My father hoarded coupons. My mother washed and reused Ziploc bags. The idea of them dropping two thousand dollars on a last-minute resort package just because Sloan was sad about a breakup felt off. It was too extravagant, even for them.

I replayed a memory from two days prior. I had stopped by their house to pick up a box of winter clothes I had left in the attic. When I unlocked the front door, the house had been loud. Sloan’s voice was echoing from the kitchen, high-pitched and frantic.

“If we do not sign by Thursday, we lose the slot!” she was shouting. “They said the penalty for backing out of the contract is huge. It is a distinctive opportunity! Dad, you just have to be there to co-sign the liability waiver.”

“I don’t know, Sloan,” my father’s voice had been hesitant. “The down payment is steep.”

“I have the cash for the deposit,” Sloan had insisted. “I just need you there physically for the membership onboarding. It is part of the deal. If I bring two guests, they waive the initiation fee.”

I had walked into the kitchen then, my keys jingling in my hand. The silence that fell over the room was immediate and absolute. It was the kind of silence that happens when a movie abruptly stops. Sloan whipped around, her face flushed, her eyes wide. She looked like a child caught with her hand in a cookie jar, but she recovered quickly, smoothing her hair and forcing a tight, plastic smile.

“Oh, hey, Aurora,” she said, her voice dropping an octave to a casual drawl. “I didn’t hear you come in.”

“What deal are you talking about?” I asked, putting my keys on the counter. “What membership?”

My father looked down at his coffee mug, refusing to meet my eyes. My mother busied herself with wiping a spotless countertop.

“Nothing,” Sloan said quickly. “Just a gym membership. They have a family plan. Boring stuff. You wouldn’t be interested. You run outside, don’t you? So free?” She emphasized the word free with a little sneer, as if my frugality was a character flaw.

I hadn’t pressed it. I just grabbed my box of clothes and left. At the time, I thought she was trying to rope them into buying a Peloton or a country club membership. But now, sitting in my apartment with the knowledge of the resort trip, the pieces began to click together with a sickening precision. A resort wasn’t just a vacation. Sloan had mentioned a contract and a penalty. She had mentioned needing them there to sign.

My phone buzzed on the desk, jarring me from my thoughts. It was a notification from Instagram. My mother had posted a new photo. I opened the app. The image was high definition and saturated with blue. It showed a view from a balcony overlooking a pristine turquoise ocean. In the foreground, three crystal flutes of champagne sat on a white linen table. The caption read: Family healing time at the Sapphire Coast. Sometimes you have to drop everything to support the ones you love. Family first. Mental health matters.

I zoomed in on the photo. In the corner of the table, half-hidden by a napkin, was a glossy brochure. I could just make out the logo. It wasn’t just a hotel. It was the Sapphire Coast Vacation Club. My stomach turned over. It wasn’t a wellness retreat. It was a timeshare presentation, or something similar—a high-pressure sales event disguised as a luxury getaway. Sloan wasn’t depressed. She was hustling. She had dragged them down there to secure some kind of buy-in, likely promising them it was an investment and she needed their credit scores or their signatures to close the deal.

But that still left one question unanswered. Sloan had said, “I have the cash for the deposit.” Sloan never had cash. Sloan lived paycheck to paycheck, supplementing her income with loans from our parents that never got repaid. If the deposit was two thousand dollars, as my mother had claimed on the phone, where did Sloan get it?

A cold, hard knot formed in my chest. I remembered something else. Four years ago, when I was a freshman, my parents had opened a joint student checking account with me. It was a requirement for the first transfer of dorm funds. Over the years, I had taken over all the deposits, but their names were still technically on the account as custodians. I used it as a holding tank for my tuition payments and book money. I hadn’t checked the balance in three weeks because I knew exactly what was in there—or at least, I thought I did.

I opened my laptop. My hands were trembling slightly, not from fear, but from a rising, icy anticipation. I navigated to the bank’s website. I typed in my username. I typed in the password I had created when I was eighteen. The dashboard loaded. I stared at the balance. It was significantly lower than it should have been. I clicked on transaction history.

There, near the top of the list, dated two days ago—the same day I walked in on them in the kitchen—was a transfer. Outgoing Wire Transfer: $2,450. The recipient was listed simply as SCVC Holdings – Sapphire Coast Vacation Club.

I sat back in my chair, the air leaving my lungs in a rush. Two thousand four hundred and fifty dollars. The number was specific. It wasn’t a round number like two thousand. It was exact and it was familiar.

I minimized the bank window and opened my student portal for Lake View State. I navigated to the financial aid section. Two weeks ago, I had received a notification about a tuition adjustment because I had dropped a lab course and picked up a seminar instead. And because I had secured an external grant for my thesis, the university had issued a refund for the overpayment I had made at the start of the semester. I pulled up the refund receipt. Credit to Student Account: $2,450. Status: Processed. Direct Deposit to account ending in 8890.

The account ending in 8890 was the joint account. The refund had hit the account on Monday morning. Sloan must have seen the notification on my parents’ phone, or perhaps my father checked the balance and mentioned it. They saw the money sitting there. My money. The money I had scraped together from double shifts and grant applications. The money I was planning to use for the security deposit on my first post-grad apartment. And they took it. They didn’t ask me. They didn’t borrow it. They simply transferred it out to pay for the deposit on the resort trip that they were using to skip my graduation.

I felt a laugh bubbling up in my throat, but it wasn’t a happy sound. It was jagged and sharp. They were literally using my own money to fund their absence. They were drinking champagne on a balcony paid for by my academic success while I sat here worrying about how I was going to afford rent next month.

I needed to be sure. I needed to be absolutely one hundred percent sure before I let this knowledge settle into my bones. I picked up my phone and dialed the number for the university bursar. It was four in the afternoon on a Friday. I prayed someone was still at the desk.

“Student Financial Services, this is Brenda.” A tired voice answered.

“Hi Brenda,” I said. My voice was calm. It sounded like I was asking about a library fine. “My name is Aurora Hill. Student ID number 459002. I am calling to verify a refund transaction.”

“One moment, honey,” Brenda said. I heard the clicking of keys. “Okay, I have your file. What is the question?”

“I see a refund of two thousand four hundred and fifty dollars processed on Monday,” I said. “Can you confirm that this money was sent to the bank account on file?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Brenda said. “Sent and cleared. It went to the First National account. We have the transaction ID if you need it.”

“And that money,” I paused, keeping my voice steady, “that was from the tuition adjustment and the external grant? Correct?”

“It was the surplus from your payments. That is correct,” Brenda confirmed. “Since you paid the initial tuition yourself via check and the grant came in later, the refund belongs to the student. Is there a problem? Did you not see it in your bank?”

“I see it,” I said. “I just wanted to confirm the source. Thank you, Brenda.”

“Congratulations on graduating, Aurora,” she added before hanging up.

“Thank you,” I said to the dial tone.

I lowered the phone. The theft was complete. It wasn’t just negligence anymore. It was predation. Sloan had needed the money to secure her deal. My parents, unwilling to dip into their own savings or perhaps unable to, had seen the influx of cash in the joint account. They probably rationalized it. They probably told themselves, “We will pay her back before she notices.” Or, “We are her parents. We have a right to manage these funds.” Or, “It is a family emergency.”

Family emergency. The emergency was that Sloan wanted a timeshare and a vacation, and I was the bank.

I looked at the screen again. I took a screenshot of the bank transfer. I took a screenshot of the university refund receipt. I opened a new folder on my desktop and named it The Truth. I dragged the files into it. I did not scream. I did not call my mother and demand an explanation. I knew exactly what she would say. She would say I was being petty about money. She would say, “We were going to tell you.” She would say, “Family helps family, Aurora.”

But I wasn’t family to them. I was a resource. I was an asset to be liquidated when the preferred child had a whim.

My eyes drifted to the graduation paperwork I had submitted just an hour ago. The names I had chosen: Tracy Simmons, Darnell Simmons, Dr. Evan Hart. A small, cold part of me had worried just for a second if I was being too harsh, if removing my parents from the ceremony was an overreaction, if I was being the “difficult daughter” they always accused me of being. That worry evaporated instantly. They had taken my money to buy the view that would distract them from my achievement. They had made me pay for my own abandonment.

I leaned back in my chair and watched the cursor blink on the screen. I wasn’t going to report the fraud to the bank yet. That would freeze the account and cause a scene while they were at the resort. It would give them a chance to play the victim, to cry about a misunderstanding and ruin my graduation day with their drama. No, I would let them enjoy the champagne. I would let them sign their contracts and feel like big shots. I would let them think they had gotten away with it. Because when my name was called on stage and the camera panned to the people who actually supported me, the humiliation they would feel would be free. But the realization of what they had lost—that was going to cost them a lot more than $2,450.

I closed the laptop. The decision was made. I wasn’t just changing a name on a slide. I was rewriting the ledger. And for the first time in the history of the Hill family, the debt was going to be collected in full.

The smell of the Simmons house was a mixture of fabric softener, garlic powder, and unpretentious chaos. It was the smell of a home that was actually lived in rather than staged for Architectural Digest. I was standing in their utility room, a basket of warm towels propped against my hip, helping Mrs. Simmons—Tracy—fold the laundry. It was a small task, a trivial task. But in my world, laundry was something my mother did in secret or sent out to a service because the sight of dirty clothes was considered an aesthetic failure. Here with Tracy, it was a rhythm. Shake, fold, stack. Shake, fold, stack.

“Mia tells me you got the highest distinction on your thesis,” Tracy said, snapping a bath towel into shape. She didn’t look up, just kept her hands moving with practiced efficiency. “She said something about narrative structures in modern media? Sounded very complicated.”

“It is sort of,” I said, smoothing a hand towel. “It is about how we curate our lives for public consumption versus private reality.”

Tracy chuckled, a warm, throaty sound. “Well, Lord knows we could all write a book about that. I still haven’t posted the pictures of the burnt lasagna from last Tuesday.”

I smiled. It was genuine. My shoulders, which had been locked in a permanent state of tension since the phone call with my parents, dropped an inch.

Mia walked in then, holding two mugs of cocoa. Mia has been my best friend since sophomore year. She is the opposite of Sloan; where Sloan is sharp angles and sharper words, Mia is soft curves and brutal honesty. She handed me a mug.

“Mom, stop making her do chores,” Mia said, leaning against the dryer. “She is a guest. She is practically a dignitary now. Magna Cum Laude.”

“I like doing it,” I said. And I meant it. There was safety in the repetition. There was safety in being useful in a way that didn’t require me to be impressive.

Darnell Simmons, Mia’s father, poked his head around the door frame. He was wearing a faded New York Giants t-shirt and holding a wrench. He had been fixing the sink in the downstairs bathroom for three hours, mostly because he liked to take breaks to watch sports highlights on his phone.

“So,” Darnell said, wiping grease onto a rag. “Big day on Saturday. We were wondering about the logistics. I know your folks are driving down, but do they need help with parking? The campus lots get full by eight in the morning. I know a spot behind the engineering building that usually stays open.”

The room went quiet, just the hum of the dryer spinning the next load. I froze. My hands were still holding the warm cotton of the towel. I hadn’t told Mia the full extent of the resort situation yet. I had only told her they were being difficult. I hadn’t told her they weren’t coming at all. I was ashamed, even though I knew it wasn’t my fault. The shame of being unprioritized feels sticky, like you are the one who failed to be worth showing up for.

I looked at Darnell. He was looking at me with simple, open curiosity. There was no judgment in his face. He just wanted to help my father park his car.

“They aren’t driving down,” I said. My voice was small, barely audible over the dryer.

“Oh, flying then?” Tracy asked. “Even worse. The airport shuttle is a nightmare.”

“No,” I said. “I…” I took a breath. I put the towel down on the washing machine. “They aren’t coming.”

“What?” Mia straightened up, her eyes narrowing.

“They went to the Sapphire Coast,” I said, the words tumbling out now, stripping away the protection I had tried to build around them. “Sloan needed a mental health break. They left this morning. They are going to watch the live stream.”

The silence that followed was different from the silence in my parents’ house. In my house, silence was a weapon used to freeze you out. Here, the silence was heavy with shock. It was the silence of people who could not process the data because it violated the fundamental laws of how they understood love. Tracy stopped folding. She put the sheet down slowly. She turned to look at me, her expression shifting from confusion to a profound, heartbreaking clarity.

“They are skipping your college graduation,” Darnell said slowly, “to go to the beach?”

“It is a wellness retreat,” I said, automatically reciting the script my mother had given me before realizing how stupid it sounded. “But yes, basically.”

I looked down at the floor, waiting for the pity. I braced myself for the Oh, you poor thing or the I am so sorry, Aurora. I hated pity. Pity made me feel small. Pity made me feel like a victim. But Tracy didn’t offer pity. She walked around the ironing board. She stood in front of me and she put her hands on my shoulders. Her grip was firm.

“Well,” Tracy said. Her voice was brisk. Matter-of-fact. “That solves the ticket problem, then.”

I looked up, blinking. “The ticket problem?”

“The university only gives four tickets per student,” Tracy said. “Mia used one for her boyfriend, one for her aunt, and we took the other two, but we were worried about where we were going to sit relative to the stage. We wanted to be close.” She looked at Darnell.

Darnell nodded, a slow, solemn nod that felt like a contract being signed. “If you have extra tickets,” Darnell said, “we would be honored to use them. We can sit in the family section. We can make some noise.”

“You don’t have to,” I said quickly. “I know you are here for Mia. You don’t have to adopt me for the day.”

“We aren’t adopting you for the day, Aurora,” Mia said, stepping forward. “You have been eating our food for three years. You fixed my dad’s resume. You helped Mom set up her Etsy shop. You are already in the ecosystem.”

“We would like to sit in your row,” Tracy corrected me gently. “Not because we feel bad for you, but because we want to see you get that diploma. We know how hard you worked for it. We remember the nights you slept on this couch with your textbooks because your dorm was too loud.”

I looked at them, the Simmons family. They were messy. They were loud. They argued about football and burnt lasagna. And they were offering me the one thing I had been starving for my entire life: presence. Not presence with conditions. Not presence that cost $2,450. Just presence.

My throat felt tight. But I didn’t cry. I nodded. “Okay,” I whispered. “I have the tickets. They are digital.”

“Send them to my phone,” Darnell said, tapping his pocket. “I will handle the parking. You just worry about not tripping on that gown.”

Later that afternoon, I sat on Mia’s back porch. The air was crisp. I had my laptop open. I had three tickets left in my allocation. The Simmons family would take two. I had one left. I thought about who else had actually been there. Not in the abstract sense, but in the trenches.

I navigated to the faculty directory and found the email address for Dr. Evan Hart. Dr. Hart was the head of the communications department. He was a terrifyingly intelligent man who wore tweed jackets and didn’t believe in grade inflation. In my junior year, I had sent him a draft of my thesis at two in the morning, panicked that the entire premise was flawed. He had replied at 2:15. He hadn’t just corrected the grammar. He had written three paragraphs of analysis, challenging my arguments, pushing me to be sharper, better. He treated my mind with a respect my parents never showed my person.

I typed the email. Dear Dr. Hart, I know this is last minute and I know you usually sit with the faculty on the stage, but it would mean a lot to me if you would accept a guest ticket to sit with my support section. My parents are unable to attend. I want to look out and see the people who actually taught me how to stand.

I hit send. I expected a polite decline. Faculty had their own protocols. Five minutes later, my phone pinged.

Aurora, I would be honored. I will trade my faculty gown for a seat in the stands. See you Saturday.

I stared at the screen. I opened the university portal again. The guest list form was locked, but the special accommodations and seating request was still open for another hour. This was where you listed the names of the ticket holders for security clearance. I typed them in. Seat 1: Tracy Simmons. Seat 2: Darnell Simmons. Seat 3: Dr. Evan Hart. Seat 4: Sarah Jenkins. Sarah was a girl I worked with at the coffee shop who had covered my shifts for two weeks during finals so I could study. She had asked for a ticket weeks ago, joking that she wanted to see me “escape.”

I looked at the list. It was eclectic. It was unconventional. It was perfect. I could have called my parents then. I could have told them, “Hey, since you aren’t coming, I gave your tickets away.” But I didn’t. I knew exactly what would happen if I did. If I told Linda Hill that the Simmons family was going to be sitting in the front row, holding the reserved spots, her vanity would override her selfishness. She would panic. She would realize how bad it would look to the neighbors, to the town. If she was absent while those people were present, she would book a flight. She would drag a complaining Sloan onto a plane. They would arrive late, stressed, and demanding credit for the “sacrifice” of coming. They would hijack the day. They would make it about their heroic arrival.

I wasn’t going to give them the chance to perform. This wasn’t about punishing them anymore. It was about protecting the peace I had just found in the Simmons’ laundry room. I wanted the people who were there because they wanted to be, not the people who were there because they were afraid of looking bad.

I closed the laptop. That night, I went back to my apartment to sleep. I needed to be alone for the last few hours before the ceremony. I hung my graduation gown on the back of the bedroom door. The black fabric seemed to absorb the light from the streetlamp outside. The gold sash shimmered faintly. I stood in front of the full-length mirror. I was wearing an old t-shirt and shorts. My hair was tied up in a messy bun. I looked at my reflection. For years, I had looked in mirrors and tried to see what my parents wanted. I looked for the obedient daughter, the low-maintenance daughter, the shadow. Tonight, I just saw Aurora. I saw the dark circles under my eyes from the double shifts I worked to replace the money they stole. I saw the set of my jaw, which was harder than it used to be. I realized I wasn’t waiting for permission anymore. I wasn’t waiting for someone to tell me I was good enough or worthy enough or important enough to warrant a flight change. I was the one who had written the thesis. I was the one who had earned the sash. I was the one who had survived the silence of that house.

My phone was on the nightstand. It started to buzz. I glanced at the screen. Mom calling. It was eleven at night. They were probably drunk on resort cocktails, calling to give me a sloppy, preemptive congratulations to assuage their guilt before they went to sleep. They wanted me to tell them it was okay. They wanted me to say, “Don’t worry, have fun. I love you.” They wanted absolution.

I didn’t reach for the phone. I watched it vibrate against the wood of the table. In the past, I would have answered. I would have smoothed things over. I would have been the bridge. I let it ring. The screen went dark. Then it lit up again with a voicemail notification. I didn’t listen to it. I picked up the phone and turned it face down on the table. The silence that filled the room wasn’t empty. It was heavy and solid. It was the first brick in the wall I was building—a wall that wasn’t designed to keep people out, but to define, finally, where I began and where they ended.

I climbed into bed. I pulled the duvet up to my chin. Tomorrow the names would be read. Tomorrow the world would see. But tonight, in the quiet dark, the victory was already mine. I fell asleep without checking the time. And for the first time in years, I didn’t dream about them.

Most people in my life think I work at a coffee shop. When I tell my family I have a part-time job at a studio, they assume I am sweeping floors or organizing files for a wedding photographer. My mother once asked me if I could print out fifty copies of a flyer for Sloan’s short-lived dog walking business because she assumed my “employee discount” would cover the ink. I didn’t correct her. In the Hill household, being underestimated was the safest way to operate. If they knew what I actually did, they would have found a way to commodify it, criticize it, or make it about them.

The truth is, for the last eighteen months, I have been working as a junior content strategist at Crestline Story Lab. It is a boutique marketing agency downtown that handles narrative campaigns for mid-sized tech companies and educational nonprofits. I started as an intern fetching coffee. But three months in, I rewrote a pitch deck for a failing client that ended up saving the account. Since then, I have been ghostwriting scripts, editing video essays, and managing cross-platform story arcs.

I was sitting at my desk on Friday morning, five hours before the Simmons family was due to arrive at my apartment. The office was buzzing with the frantic energy of a launch day. My dual monitors were glowing with analytics dashboards.

“Aurora,” a voice called out.

I looked up to see Julian, the Senior Creative Director, standing at the door of his glass-walled office. He waved me over. Julian was a man who spoke in bullet points and drank four espressos before nine in the morning. He didn’t waste time on pleasantries. I grabbed my notebook and walked in. I assumed he wanted revisions on the copy for the insurance client we were onboarding.

“Close the door,” he said, pointing to the chair opposite his desk.

I sat down. My heart gave a small, traitorous thud. Had I messed up? Had the tuition refund issue somehow bled into my background check? Paranoia was a side effect of living with my parents; you always assumed the other shoe was about to drop.

Julian spun his monitor around so I could see it. “Recognize these numbers?” he asked.

I looked at the screen. It was the engagement report for the Horizon Project, a multimedia campaign for a national educational software brand called Lumina Learning. I had written the core narrative, a series of six interrelated short films about students overcoming learning barriers. It was the project I had been working on late at night, the one Sloan had mocked when she saw me typing furiously at the kitchen table over Christmas.

“The engagement rate is sitting at twelve percent,” I said, reading the graph. “That is good. The industry benchmark is four.”

“It is not good, Aurora,” Julian said, his face deadpan. Then he cracked a rare, wide grin. “It is a record. The third video went viral on TikTok last night. Two million views in twelve hours. The client is losing their mind. They said the narrative voice was raw, authentic, and piercing. That was your script.”

I felt the blood rush to my cheeks. “I am glad they liked it.”

“They didn’t just like it,” Julian said, leaning back. “They want to lock down the voice, and Crestline wants to lock down the talent.” He slid a thick envelope across the desk. It was heavy, creamy paper. “We are offering you a Junior Associate position, effective immediately upon your graduation. Starting salary is sixty-five thousand dollars a year, plus full benefits and a signing bonus. We drafted the contract this morning.”

I stared at the envelope. Sixty-five thousand dollars. It was more money than my father made at his mid-level management job. It was freedom. It was an apartment with a lock on the door. It was a car that didn’t break down.

“Thank you,” I managed to say. “I don’t know what to say.”

“Don’t say anything yet,” Julian interrupted, holding up a hand. “There is more. Since you are graduating tomorrow from Lake View State, and since Crestline is a Platinum Donor to the university’s media department, we want to make a scene.”

“A scene?” I repeated, the word triggering a reflex of anxiety.

“Marissa Vale is going to be there,” Julian explained. Marissa was the CEO of Crestline. She was a legend in the industry, a woman who had turned a small blog into a media empire. “She is doing the guest presentation after the diplomas. We want to announce your hiring and the success of the Horizon Project live on stage. We are creating a new award, the Crestline Emerging Voice Award. You are the first recipient.”

My hands were gripping the arms of the chair. This was huge. This was the kind of career launch most students only dreamed of.

“It comes with a grant,” Julian continued. “Five thousand dollars cash, separate from your salary. And, naturally, we want to acknowledge the support system that got you here.”

The air in the room seemed to shift. “Support system?” I asked.

Julian pulled a clipboard from a stack of papers. “Marissa is big on the ‘it takes a village’ philosophy. We have a VIP package for the parents of the award recipient. Front row seating upgrades if they aren’t already there. A mention in the speech. And a thank-you gift from the company. It is a weekend getaway package to a luxury lodge in Vermont. Fully paid. We like to treat the families who raised our talent.”

I stared at the clipboard. A weekend getaway. Fully paid. The irony was so thick I could almost taste it. My parents had stolen $2,450 from me to pay for a discount resort trip. And if they had just shown up—if they had just done the bare minimum of being present—they would have been handed a luxury vacation worth three times that amount.

“I need you to sign the release form,” Julian said, tapping the paper with a pen. “And fill in the names of the family members attending so we can have the host call them out. Are your parents coming?”

I looked at the form. It had two lines under the header Honored Guests. I thought about the empty seats. I thought about the text message my mother had sent ten minutes ago: The buffet here is incredible. Hope you are studying hard. They weren’t studying. They were eating shrimp and ignoring my existence.

“My parents couldn’t make it,” I said. My voice was steady. It didn’t waver. “They had a prior commitment.”

Julian’s eyebrows shot up. “They are missing your graduation? And this award?”

“Yes,” I said.

“I see,” Julian said. He didn’t pry. He was a professional. “Well, is there anyone else? A mentor? A guardian? We really want that shot of the proud supporter in the crowd. It plays well on the live stream.”

“Yes,” I said. “There is.”

I took the pen. I didn’t hesitate. I wrote the names in clear block letters: Tracy Simmons. Darnell Simmons. Underneath, in the section for Relationship to Recipient, I paused. Technically, they were my best friend’s parents. But what is a parent? Is it biology? Or is it the person who taught you how to fold a towel and offered you a seat when your own blood left you standing? I wrote: Chosen Family.

“And just so you know,” Julian added, watching me write, “the gift, the Vermont trip? It is transferable. Whoever you list there gets the voucher. It is in the envelope we hand them on stage.”

My pen stopped moving for a fraction of a second. This was it, the final nail. Not only was I giving the Simmons family the public credit, I was giving them the financial reward my parents would have killed for. My father would have bragged about this trip for years. My mother would have posted a hundred photos. Sloan would have tried to come along. By giving it to the Simmons, I wasn’t just snubbing my parents. I was denying them a tangible asset.

“Is that a problem?” Julian asked, seeing my hesitation.

“No,” I said, finishing the signature with a flourish. “No problem at all. They are the ones who deserve it.” I handed the clipboard back.

“Great,” Julian said, checking the names. “We will get the production team to update the teleprompter. We have a dedicated camera operator who will find them in the crowd during the speech. Make sure they know to look surprised.”

“They will be surprised,” I said. “They have no idea.”

“Perfect,” Julian said. “Authentic emotion. That is what we sell.” He stood up and shook my hand. “Congratulations, Aurora. You are going to be a star. Don’t let the fame go to your head.”

“I won’t,” I said. “I am just trying to keep my feet on the ground.”

I walked out of his office and back to my desk. The office noise washed over me—the ringing phones, the clatter of keyboards, the low hum of collaboration. It felt different now. It didn’t feel like a place I was hiding in. It felt like my territory. I sat down and opened my email. A message from the production team had already landed.

Subject: Run of Show. Urgent. Time 11:45 AM. Crestline Awards Segment. Action: Aurora Hill to Center Stage. Camera 2 to pick up guests (Simmons). Audio: Voiceover by Marissa Vale.

I read it twice. I thought about calling my parents. I thought about giving them one last chance. I could say, “Hey, I am getting an award and there is a free trip involved. Get on a plane right now.” If I did that, they would come. They would sprint. They would leave Sloan at the resort and fly to me, not because they loved me, but because they loved winning. They would stand on that stage and beam, and they would take the voucher, and they would tell everyone, “We always knew she was special.” And I would be the shadow again. I would be the prop in their success story.

I looked at the phone. “No,” I said to the glowing screen. I wasn’t their investment anymore. I was my own.

I hit reply to the production email. Confirmed. The names are correct. See you tomorrow.

I shut down my computer. I packed my notebook. I put the contract in my bag. As I walked to the elevator, I felt a strange sensation in my chest. It wasn’t guilt. It was the feeling of a heavy weight being cut loose, falling away into the deep, leaving me buoyant. My parents were at a resort, chasing a deal that would cost them money. The Simmons were about to walk into a ceremony and receive a deal that would pay them back for kindness they gave for free. It was poetic justice. It was narrative symmetry. And as a professional storyteller, I knew better than to ruin a perfect ending with a last-minute edit.

The morning of the ceremony arrived with a sky the color of a bruised peach, hazy and humid. I woke up before the alarm. The silence in my apartment was absolute, a stark contrast to the chaotic symphony of nerves and preparation happening in thousands of other homes across the state. In other houses, mothers were currently steaming gowns and fathers were charging camcorder batteries. In my house, the only sound was the coffee maker gurgling its final breath.

My phone, resting on the nightstand, lit up. It was seven in the morning. I picked it up. A photo from my mother. It was a masterpiece of composition. A sweating glass of iced tea sat on a teak table, flanked by a rolled-up white towel and a pair of designer sunglasses. Beyond the railing, the ocean was a flat, aggressive turquoise. The caption read: Morning view. Thinking of you today. Wish you were here to relax with us.

I looked at the pixels. I looked at the performative relaxation. Wish you were here. It was a lie. If they wished I was there, they would have bought me a ticket. If they wished to be with me, they would be standing in a parking lot in Marlin Bay right now, fighting for a space. What they meant was, “We wish you were part of this backdrop so we could feel like a complete set, but we are perfectly content to enjoy the buffet without you.”

I did not type a reply. I did not send a sad emoji. I did not send a sarcastic remark about the humidity. I simply swiped the notification away. It felt like brushing a fly off my arm.

I stood up and began the ritual. I put on the navy blue dress. I pulled the black polyester gown out of its plastic sheath. It smelled faintly of industrial chemicals and storage—a scent that somehow felt like dignity. I zipped it up. I adjusted the gold sash, the heavy fabric settling across my chest like a shield. I went to the mirror to pin my cap. Usually, this is a two-person job. Usually, a mother stands behind the daughter, her mouth full of bobby pins, fussing with stray hairs, telling her to stand up straight. I picked up the bobby pins. My hands were steady. I parted my hair. I slid the metal clips in, securing the mortarboard to my skull so tight a hurricane couldn’t knock it loose.

I looked at my reflection. There was no one behind me in the mirror. No shadow, no criticism. Just me. I took my phone, held it up, and snapped exactly one photo. I didn’t smile. I looked straight into the lens, my chin slightly lifted, my eyes clear. I didn’t post it to Instagram. I didn’t send it to the family group chat. I saved it to the hidden folder on my camera roll. That photo was for the Aurora who would exist ten years from now, proof that she had stood alone and hadn’t crumbled.

The drive to the university arena was a blur of traffic and brake lights. When I walked into the staging area, the noise hit me like a physical wave. It was a roar of excitement—shouts, laughter, names being called, zippers zipping. I found my place in the line, H. I was wedged between a guy named Hernandez, who smelled like expensive cologne, and a girl named Higgins, who was hyperventilating into a paper bag.

Reflex is a difficult thing to kill. As we marched into the main arena, the lights blindingly bright overhead, my eyes automatically scanned the upper mezzanine. It was the section where families with general admission tickets sat. My brain was looking for my father’s bald spot. My brain was looking for my mother’s frantic waving. I stopped myself. The realization hit me again, cooler this time. They are not there. And for the first time in my life, the absence didn’t feel like a hole. It felt like space. It felt like the room you get when you finally throw out a piece of furniture that you kept tripping over.

We filed into the rows of folding chairs on the floor. I sat down. I looked to the left, toward the VIP and reserved seating section near the front. And then I saw them.

In Row 4, Seat 1: Tracy Simmons was wearing a floral dress that was brighter than anything my mother would ever dare to wear. She was holding a pack of tissues in one hand and a program in the other. She was scanning the graduates, her neck craning, looking for me with the intensity of a searchlight.

Next to her, Darnell Simmons was wearing a button-down shirt and a tie. Darnell hated ties. He complained about them at weddings and funerals. But today, for a ceremony that wasn’t for his own child, he was wearing a tie. He looked uncomfortable, and he looked magnificent.

And next to him sat Dr. Evan Hart. He wasn’t wearing his academic regalia. He was in a tweed suit, looking distinctly out of place among the cheering families, yet he was leaning in, listening to something Darnell was saying.

Tracy saw me. She didn’t just wave. She stood up. She grabbed Darnell’s arm and pointed. She mouthed my name. Darnell gave me a thumbs up that was so enthusiastic he nearly elbowed the person next to him. I felt a lump form in my throat. But it wasn’t the sharp lump of grief. It was the warm, expanding lump of gratitude. I raised my hand and waved back.

Suddenly, a hand touched my shoulder. I turned. It was Dr. Hart. He must have slipped away from the stands to come down to the student barrier before the speeches began. The security guard was eyeing him, but Dr. Hart had the kind of authority that made security guards hesitate.

“Aurora,” he said, his voice cutting through the din.

“Dr. Hart,” I said. “You didn’t have to come down here.”

“I wanted to make sure the sash was straight,” he said, though he didn’t reach out to touch it. He looked me in the eye. “You did the work, Hill. All of it. The thesis, the late nights, the revisions.”

“Thank you,” I said.

He leaned in closer, his voice dropping so only I could hear. “I know your parents aren’t here. I know that feeling. But look at that row over there.” He gestured vaguely toward the Simmons family. “Today, you do not owe anyone smallness. Do you understand? You take up as much space on that stage as you need.”

“I will,” I whispered.

He nodded, tapped the barrier once, and disappeared back into the crowd.

The ceremony began. It was long. The dean spoke about future leaders. The valedictorian spoke about memories. I heard none of it. I was in a trance state, a hyper-focused reality where every sound was magnified. I heard the rustle of programs. I heard the squeak of shoes on the basketball court floor. My heart was beating a rhythm against my ribs: one, two, one, two.

Then the reading of the names began. Adams. Allan. Anderson. Each name was followed by a burst of noise from a specific pocket of the arena. Air horns, screams. That is my baby! I watched the students walk across the stage. Some danced, some cried, some looked terrified. Hernandez. The guy next to me stood up.

I was next.

“Aurora Hill.”

The name rang out over the PA system. It sounded different than when I said it. It sounded official. I stood up. My legs felt solid. I walked to the ramp. The lights were hot on my face. I could feel the cameras tracking me. I knew that three hundred meters away, in a hotel room that cost five hundred dollars a night, a laptop screen was flickering.

I stepped onto the stage. I didn’t look down at my feet. I looked out. I saw the sea of faces. I saw the flashbulbs. And then, down in front, I saw Tracy Simmons standing up again, waving her program like a flag. I saw Darnell cupping his hands around his mouth, shouting something I couldn’t hear but could feel in my bones. I saw Sarah, my coworker from the coffee shop, whistling with two fingers.

I walked toward the dean. I reached out my hand. I took the diploma folder, and then I smiled. It wasn’t the polite, closed-mouth smile I used in family photos to avoid criticism about my teeth. It wasn’t the apologetic smile I used when I asked for a loan. It was a smile that bared my teeth. It was radiant. It was fierce. It was the smile of someone who had just climbed a mountain carrying a backpack full of rocks, dumped the rocks at the summit, and realized she could fly.

The camera on the jib arm swooped down, capturing that face. I looked right into the red tally light. Hello, Mother. Hello, Father. Hello, Sloan. This is what I look like when I’m free.

I walked off the stage. The applause for me hadn’t been the loudest in the room, but it had been the most real. I went back to my seat. I sat down. I put the diploma in my lap. I traced the gold lettering of the university seal. I thought it was over. I thought the climax had passed. I was ready to sit through the remaining two hundred names, go out for a burger with the Simmons family, and start my life.

But the flow of the ceremony stopped. The Master of Ceremonies, a man with a deep baritone voice, returned to the podium. He didn’t call the next name. He held up a hand to quiet the crowd.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, “please remain seated. We have a brief interruption to the procession for a very special presentation.”

A murmur went through the crowd. Students looked at each other. This wasn’t in the rehearsal.

“Lake View State is proud to partner with industry leaders,” the MC continued. “And today, in collaboration with Crestline Story Lab, we are honored to present the inaugural Emerging Voice Recognition.”

My heart stopped. I had forgotten. In the rush of the walk, in the adrenaline of the diploma, I had completely forgotten about Julian and the award.

“This recognition,” the MC said, “is awarded to a student whose work has not only excelled academically but has already made a significant impact in the professional world. A student whose narrative strategy has reached millions.” He looked at his cue card. “Please welcome to the stage the CEO of Crestline Story Lab, Ms. Marissa Vale.”

Marissa walked out. She was striking, wearing a white power suit that glowed under the stage lights. She took the microphone. The screens behind her changed. The logo of the university was replaced by the Crestline logo. And then a massive, high-definition image of my face—the headshot I had used for my company badge—appeared on the Jumbotron. A gasp rippled through the student section.

“Aurora Hill,” Marissa said, her voice commanding. “Would you please return to the stage?”

I stood up again. My knees were shaking now. This was different. This wasn’t just graduating. This was being chosen. I walked back up the stairs. Marissa met me halfway. She shook my hand and turned me toward the audience.

“Aurora,” she said into the mic. “Your work on the Horizon Project defined the semester. You have a gift. And at Crestline, we believe that behind every great storyteller, there is a story of support.” She gestured to the crowd. “We know you didn’t get here alone.”

Marissa said, “We know there are people who sacrificed, who encouraged, and who showed up.”

I stood there, freezing. I knew what was coming. The audience knew what was coming. They expected the standard script. They expected the camera to find a weeping mother and a proud father.

“We asked Aurora to identify the family members who made this day possible,” Marissa said. “The people she wanted to honor with our Distinguished Support Package, which includes a fully paid vacation to the Vermont Exalted Lodge.”

The word “vacation” caused a ripple of excitement in the crowd. “So,” Marissa said, smiling at me, then looking out at the darkness of the arena. “Will the family of Aurora Hill please stand up?”

The spotlight operator was ready. The camera operator was ready. They had the coordinates I had given Julian. Row 4, Seat 1 and 2.

The giant spotlight swung through the smoky air. It bypassed the empty section where the ‘H’ families were supposed to be. It swept across the floor. It landed, blindingly bright, on Row 4.

Tracy Simmons froze with a tissue halfway to her nose. Darnell Simmons blinked, his mouth falling open. The camera feed on the Jumbotron switched. Suddenly, the entire arena was looking at Tracy and Darnell.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Marissa announced, her voice booming. “Please give a round of applause for Aurora’s support system! The people who were there!”

The crowd cheered. They didn’t know who Tracy and Darnell were. They just saw two people looking shocked and humble. But I knew. And three hundred meters away, staring at a laptop screen in a resort suite, three other people knew. As the applause swelled, masking the sound of my own heartbeat, I realized that the phrase “her parents” had just been publicly, irrevocably redefined. The biological contract had been voided. The social contract had been signed.

And the best part? The camera was zooming in.

The silence in the arena was different now. It was no longer the restless, shifting silence of three thousand people waiting for a ceremony to end so they could go eat lunch. It was a dense, electrified silence. Marissa Vale stood at the podium, her white suit catching the stage lights, looking less like a corporate executive and more like a prosecutor about to deliver a closing argument. She didn’t look at her notes. She looked directly into the camera lens, the red tally light glowing like a vigilant eye.

“We talk a lot about potential in this room,” Marissa began, her voice amplified and crisp, echoing off the high rafters. “But potential is just energy waiting for a direction. At Crestline, we don’t look for potential. We look for kinetic force. We look for the people who are already moving.”

She turned slightly, extending a hand toward me. I was standing a few feet away, clutching my diploma folder so hard I could feel the cardboard bending. The heat from the overhead rig was intense, pressing down on my shoulders, but I didn’t sweat. I felt cold, crystallized, like I was made of glass.

“Aurora Hill did not just complete an internship with us,” Marissa continued. “She architected the narrative backbone of our largest national campaign for the coming fiscal year. The Horizon Project, which launched seventy-two hours ago, has already garnered engagement metrics that veteran strategists spend careers chasing. She told a story about resilience that resonated because it was true.”

A ripple went through the seated graduates. They knew the project. They had seen the ads on their feeds. They whispered to each other, “That was her.”

Marissa smiled, a sharp, professional expression. “Because of this, Crestline Story Lab is not just giving an award today. We are offering a future. I am pleased to announce that as of nine o’clock this morning, Aurora has been signed as our newest Associate Narrative Lead.” She paused for effect. “This position comes with a starting salary of sixty-five thousand dollars a year, a full benefits package, and a signing bonus of ten thousand dollars.”

The gasp was audible. In a room full of students facing student loan debt and an uncertain job market, sixty-five thousand dollars sounded like a lottery win. A low whistle cut through the air. Someone in the back shouted, “Get it, girl!”

My face remained impassive, but inside I felt a vindictive thrill. I knew my parents were watching. I knew my father, who obsessed over starting salaries and stability, was sitting in that hotel room doing the mental math. I knew my mother, who loved to brag about money she didn’t earn, was probably already typing a Facebook status about her daughter’s success. They were about to realize that this success had a gatekeeper, and they did not have the key.

“But,” Marissa said, her voice dropping to a warmer, more intimate register. “No one builds a foundation alone. We know that behind every sleepless night, every deadline met, and every creative breakthrough, there is a support system. There are the people who kept the coffee brewing, who answered the phone at midnight, and who believed in the vision before the rest of the world saw it.”

The camera on the Jumbotron cut to a wide shot of the audience. It panned slowly over the families in the stands, mothers wiping tears, fathers holding up iPads.

“Crestline believes in honoring that village,” Marissa announced. “We invited Aurora to name the people who have been her rock, the people who are here today—not out of obligation, but out of love. We have a special recognition for them, a token of our gratitude, including a fully expenses-paid week at the Vermonter Luxury Lodge, valued at five thousand dollars.”

The crowd murmured again. A five-thousand-dollar vacation. I saw the camera operator down in the pit adjust his focus. He was getting ready.

“So,” Marissa said, opening a sleek black envelope she had been holding. “Would the following guests please rise and join us on stage to accept this recognition?”

I took a breath. This was it. The moment the bridge burned. The moment the boat left the dock.

“Tracy and Darnell Simmons,” Marissa read clearly. “And Dr. Evan Hart.”

The silence that followed was not the electrified silence of before. It was a confused, heavy vacuum. The audience in the general admission stands craned their necks. They were looking for a couple that looked like me. They were looking for the standard “Mom and Dad.”

The camera swung violently to the left, zooming in on Row 4 on the giant screen. The faces of Tracy and Darnell Simmons appeared. They were massive. Every pixel of their shock was visible to five thousand people. Tracy’s mouth was slightly open. She looked to her left, then to her right, as if searching for another Tracy Simmons. Darnell was halfway out of his chair, frozen in a crouch, his eyes wide and panicked. Even Dr. Hart looked momentarily stunned, adjusting his glasses as if to check he had heard correctly.

For three seconds, nobody moved. The arena held its breath. I turned my head. I looked directly at them. I didn’t smile. I locked eyes with Tracy across the distance. I saw the question in her eyes: Us? Really? Us?

I nodded. It was a small, decisive movement, a confirmation. Yes, you.

That nod broke the spell. Darnell stood up fully. He straightened his tie with a trembling hand. He offered his arm to Tracy. She took it, her other hand clutching her chest. Dr. Hart stood up on the other side, buttoning his tweed jacket with academic dignity. They stepped into the aisle.

A low murmur started in the crowd. People were confused. Who are they? That doesn’t look like her parents. But then Darnell looked at me. He wasn’t looking at the camera. He wasn’t looking at Marissa. He was looking at me with a pride so raw and luminous it could have lit the entire stadium. He smiled. And it was the smile he gave Mia when she learned to ride a bike. The smile he gave me when I fixed his resume. The crowd saw it. They didn’t know the backstory. They didn’t know about the resort or the stolen money. They just saw love, and love, when it is genuine, is recognizable from the nosebleed seats.