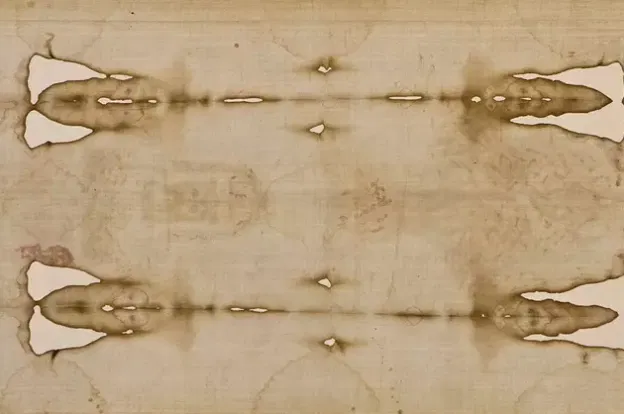

For a long time, religious, historical, and scientific groups have been particularly interested in and disputed about whether the Shroud of Turin is real. This old piece of linen, which was first mentioned in historical documents around 1353, has a faint picture of a man with wounds that seem a lot like the ones in the Bible when Jesus Christ was crucified. There are marks on the material that look like cuts on the wrists and feet, and there are also marks that seem like a crown of thorns. Many Christians thought that the Shroud could be the fabric that covered Jesus’s body after he died because of these things.

For hundreds of years, this idea was immensely significant to people’s spiritual and cultural lives. Many individuals thought the Shroud was a sacred thing. The linen is a mystery because of its past and the peculiar, unexplained method the image was formed. But a new study in the journal Archaeometry gives us new evidence that goes against what people have traditionally thought: that the Shroud physically touched Jesus’s flesh.

Cicero Moraes is a Brazilian 3D artist that makes historical faces look like they did in the past. He used advanced computer modeling to look at the face of the Shroud. He pretended to drape cloth over two different shapes: a genuine human body and a low-relief sculpture, which is a surface with little bumps that seem like wood carvings or stone engravings. Moraes said that these digital fabric simulations were like black-and-white pictures of the Shroud from 1931. He thought that the way the cloth hangs over a low-relief sculpture seems more like how it would hang over a real human body.

This finding suggests that the image on the Shroud may not have been made by touching a real body, but rather by utilizing a molded shape. Moraes said in an email interview that the picture on the Shroud appears like what would happen if the cloth were stretched over a low-relief matrix consisting of wood, stone, or metal. It is possible that this type of matrix was dyed or heated where it touched the fabric to make the pattern on the cloth.

When Moraes created a three-dimensional body look like it was covered in cloth, the fake cloth changed shape and size in ways that didn’t match the Shroud image. When the material was stretched over a shape with little relief, it didn’t expand or change shape. This supports the notion that the appearance of the Shroud may be an artistic fabrication rather than an authentic body imprint.

Moraes says that there is a small chance that the picture is an impression of a real human body, but he stresses that it is more likely that artists or sculptors with the right skills made the Shroud to look like that, either by painting techniques or by using a low-relief matrix. This new proof takes the conversation beyond just religious speculation to art history and scientific inquiry, giving us new ways to think about how the Shroud might have been made.

These new findings are consistent with carbon dating examinations from the late 1980s, which indicated that the fabric of the Shroud was produced between 1260 and 1390 A.D. This timeline shows that it was made a long time after Jesus’ time. This supports the idea that the Shroud is not a real first-century relic but a medieval artifact. We still don’t know where the Shroud came from, but Moraes’ discovery adds to a growing body of evidence that it may have been an artistic portrayal meant to inspire devotion rather than an actual burial shroud.

People are still very interested in and passionate about the controversy over the Shroud of Turin. This is because it makes us think more about faith, history, and how science and belief are connected. Moraes’ work challenges our beliefs and helps us see the Shroud as more than just a religious symbol. People made it, and history influenced it, so it’s also a complicated thing.